The shortest reign in British history

Lady Jane Grey was Queen of England for just nine days, from 10 July to 19 July 1553. She was proclaimed Queen as part of an unsuccessful bid to prevent the accession of her Catholic cousin, Mary Tudor. The great-granddaughter of Henry VII, Jane inherited the crown from her cousin Edward VI.

Jane arrived at the Tower of London to prepare for her coronation, but within a fortnight she was back as a prisoner of Mary I who had claimed the throne as rightfully hers. While Mary was reluctant to punish her at first, Lady Jane proved too much of a threat as the focus of Protestant plotters intent on replacing Mary.

On 12 February 1554, Lady Jane Grey was executed on Tower Green at the Tower of London. She was 17 years old. Did she die an innocent victim of the men plotting around her? Or as a willing Protestant martyr?

Did you know?

It is likely that Lady Jane Grey was named after Henry VIII's third wife, Jane Seymour.

Image: Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, © The Stapleton Collection

The birth of Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey was born sometime in the autumn of 1537, the eldest daughter of Lady Frances and Henry Grey, 3rd Marquess of Dorset.

Hers was a high-status family – both her parents were frequently at court. Jane's mother, Lady Frances was the daughter of Mary Tudor, Henry VIII's youngest sister. Through her grandmother, Lady Jane Grey was directly linked to the King, Henry VIII.

Lady Frances and Henry Grey, 3rd Marquess of Dorset, had three daughters: Lady Jane, Lady Katherine and Lady Mary. The family lived at Bradgate House in Leicester.

Image: Lady Jane Grey by Unknown artist, c1590-1600, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Early life and education

Like other girls in her position, Jane received a strict but good education at home.

She learnt classical languages such as Greek, Latin and Hebrew as well as French and Italian, and through her father and tutors, was exposed to Protestantism.

Jane was a dedicated student and preferred reading Plato over sports and hunting.

When asked why she was not outside, she replied: ‘I wist all their sport in the park is but a shadow to that pleasure that I find in Plato. Alas, good folk, they never felt what true pleasure meant.’

Move to the Seymour household

In the spring of 1547, when she was 10, Jane was sent to the household of Thomas Seymour.

It was common in the Tudor period for aristocratic children to be brought up in other households, especially if the ‘foster family’ was of a higher status. The children learnt etiquette and were in an advantageous position to find a suitable patron or to make a good marriage.

Did you know?

‘Fostering’ aristocratic children enhanced a family’s influence and their finances, as there was money to be made from matchmaking.

Image: Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley by Nicolas Denisot. © Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

The ambition of Thomas Seymour

Thomas Seymour (c1508-1549) was a close family friend, but most importantly, he was the uncle of the new king, Edward VI (his late sister was Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third Queen).

The ambitious Thomas realised that having Jane under his influence could be extremely profitable. Both Jane and Edward were still children, but when they reached maturity Thomas planned to marry Jane to the King.

Image: Katherine Parr by an unknown artist, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Katherine Parr's influence on Jane

Around the same time in 1547, Thomas Seymour married Katherine Parr, the late King's widow. Katherine was close to Henry VIII's children, and personally oversaw their education.

She was a keen Protestant and an educated woman, a patron of the arts and music.

She made sure to share these interests with her stepchildren and Lady Jane Grey, who blossomed into an intelligent, cultured and pious young woman.

Sadly, Katherine died in childbirth in September 1548, and Jane was sent home. However, it wasn’t long before she returned to Thomas Seymour’s household.

As third in line to the throne, Jane was a valuable asset, especially if she married the King, Edward VI. Thomas Seymour wanted to keep her close.

The rise and fall of the Seymour brothers

Meanwhile, a new reign had started. Edward VI was nine years old and too young to rule by himself, so a Council of Regency was formed, led by Edward VI's uncle, (and Thomas Seymour's elder brother) Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset.

As the young King's Protector, Edward Seymour exploited his powerful position, much to the annoyance of the Council and especially his younger brother, Thomas Seymour, who wanted the role for himself.

Driven to desperate action to get close to the boy King, Thomas tried to break into Edward VI's private apartments on the night of 16 January 1549.

This moment of idiocy proved disastrous for the impulsive Thomas Seymour. He was arrested, sent to the Tower of London and executed on Tower Hill on 20 March 1549.

Lady Jane Grey was sent home, with no prospects of marrying the King.

Lord Protector under threat?

Meanwhile, Edward Seymour's rule of England on behalf of the King Edward VI was a disaster. By 1549 the country was nearly bankrupt.

The other members of the Council united against him, under their emerging leader John Dudley, who became Earl of Northumberland.

Did you know?

In October 1549, the members of the Council tried to remove Edward Seymour from power.

The execution of Edward Seymour

Edward Seymour held the King at Hampton Court Palace 'for his protection' then spirited him away to fortified Windsor. However, lack of provisions meant they nearly starved. He capitulated, was arrested and charged. Edward Seymour was eventually executed at the Tower of London in January 1552.

By this time, a collective governorship was in place, led by John Dudley, which was more successful at running the country. The King, growing in confidence and becoming more assertive, hastened the pace of religious reform and started to think about a Protestant successor.

Image: Edward VI attributed to William Scrots, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, RCIN 405751

The King’s plans for succession

In January 1553, the 15-year-old Edward VI fell ill with a fever and a cough. From then on, his health remained volatile. It would take turns, sometimes seeming to improve, only to worsen again.

Worried about the fate of the Crown, he wrote his ‘Devise for the Succession.’ Inspired by his father’s own will, it took Edward several drafts to complete. The first version was written before he realised his illness was terminal, and it did not single out Jane as his heir.

Edward wanted above all to ensure that his successor was a male Protestant, so he disinherited his half-sisters Mary and Elizabeth in favour of the male heirs of his cousin, Lady Frances Grey or of her children, Jane, Catherine and Mary.

By June 1553 it became clear that the King was fatally ill. Since none of his cousins had yet produced a male heir, he changed his ‘devise’ in favour of Lady Jane Grey.

Although Jane would reign as queen, the crown could only follow to a male heir. If Jane died without sons, then it would go to the son of one of her sisters.

Edward’s second version was signed by the Privy Council and at least ten of the country’s senior lawyers.

Lady Jane marries Lord Guildford

This new version of Edward’s ‘devise’ was highly advantageous to the King’s Protector, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland.

It may have been all part of his master plan, as earlier that year he had married off Jane to his son, Lord Guildford Dudley, so that when Edward VI died the couple would become king and queen. Jane was 16 when she married, and Guildford aged about 18.

In any event, the marriage of Jane and Guildford on 25 May 1553 was beneficial to both families. After the King, the Duke of Northumberland was the most powerful man in England.

Image: Portraits of Lady Jane and Lord Guildford Dudley by Richard Burchett, © Parliamentary Art Collection, WOA 1008.

'A wife who loves her husband'

Lady Jane got married alongside her sister Catherine Grey and her sister-in-law Catherine Dudley in a triple ceremony at Durham House.

We don’t know much about their married life. Jane described herself as ‘a wife who loves her husband’ and she admitted that she resented her mother-in-law, the Duchess of Northumberland's, control over her husband, Guildford.

The death of Edward VI

Edward VI’s brief but eventful reign came to a premature end on 6 July 1553, when he was only 15 years old.

On Sunday 9 July, Jane was summoned to Syon House, her father-in-law’s London residence, to be told that according to Edward’s instructions, she was now to be crowned queen.

This appeared to come as a huge surprise to Lady Jane, who became very distressed, which confused and embarrassed the Privy Councillors who knelt before her to swear allegiance.

Did you know?

Edward VI succumbed to what is thought to have been tuberculosis.

Image: Lady Jane Grey Prevailed on to Accept the Crown by Charles Robert Leslie, © Tate CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)

Lady Jane Grey is proclaimed queen

Lady Jane would not be calmed until her parents and husband arrived. Jane later described that event:

‘Declaring to them my insufficiency, I greatly bewailed myself for the death of so noble a prince, and at the same time, turned myself to God, humbly praying and beseeching him, that if what was given to me was rightly and lawfully mine, his divine Majesty would grant me such grace and spirit that I might govern it to his glory and service and to the advantage of this realm.’

Image: Lady Jane Grey (1536-54) after a painting by Herbert Norris, © Lebrecht Music & Arts/Alamy Stock Photo

Procession to the Tower

The following day, Jane, Guildford, her parents, mother-in-law and other court ladies entered the Tower of London by the Lion Gate, on a procession of barges to prepare for her coronation. It was customary for new English monarchs to reside in the Tower from the time of accession to their coronation.

The group must have looked splendid. Jane was wearing a green velvet dress embroidered in gold, with a long train carried by her mother.

Her headdress was white, heavily decorated with jewels, and on her neck a chinclout (a type of scarf) ‘of black velvet, striped with small chains of gold, garnished with small pearls, small rubies and small diamonds … furred with sables and having thereat a chain of gold enamelled green, garnished with certain pearls.’

As she walked, a canopy was carried over her head. Guildford, tall and blond, was next to her, wearing white and gold.

A reluctant queen

Everything seemed to go smoothly until the time Jane was asked to wear the crown. She refused and recalled being told she ‘could take it without fear and that another also should be made, to crown my husband. Which thing I, for my part, heard truly with a troubled mind, and with ill will, even with infinite grief and displeasure of heart.’

Guildford wanted to be proclaimed king, but Jane would not do so without an Act of Parliament. Instead, she made him Duke of Clarence, to her mother-in-law’s fury.

Did you know?

Jane's mother-in-law ordered her son home to demand to be made king, but with now the ultimate power, Jane insisted he stay at court.

Image: Queen Mary I by Hans Eworth, 1554, © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Mary I's revenge

Before Jane could settle the issues with her husband, her reign came to an end. Her cousin Princess Mary, oldest daughter of Henry VIII, wrote to the Privy Council demanding to be made queen.

The Council members, the Archbishop of Canterbury and many other powerful men, all fatally underestimated the strength of support for the Catholic princess. They sent a joint reply backing Jane, and advising the Princess to be ‘quiet and obedient’.

However, Mary was her father’s daughter; a princess with much popular support as the lawful claimant to the throne. As it dawned on the Council that Mary might be a bigger threat than they thought, they allowed John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, (and one of the best military men in the country) to raise a small army to capture Mary at Framlingham Castle.

Mary I overthrows Jane Grey to become Queen

Mary wasted no time in raising a larger army of her own, and although John Dudley was a superb soldier, he decided to retreat. Mary was very popular amongst the Catholics and had the support of all those who believed in her lawful claim to the throne as Henry VIII’s daughter.

Even before Dudley had returned to London the Council had swung in support of Princess Mary. On 19 July 1553, Mary was proclaimed Queen Mary I, to the great rejoicing of Londoners.

Aware of the danger, Jane’s father rushed to proclaim Mary on Tower Hill, leaving Jane and Guildford inside the Tower. Her mother and her ladies-in-waiting also abandoned the young couple.

From this moment onwards everyone was trying to save their own heads, which makes it hard today to unravel the truth as facts were changed to protect the guilty.

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, the principal councillor, became the scapegoat.

'May I Go Home?'

Lady Jane Grey's First Moments as a Tower of London Prisoner

In this blog post, Jane's biographer Dr Nicola Tallis unpicks the moment that Jane learned of her deposition and was forced to come to terms with her fall from Queen to Tower prisoner.

From palace to prison

After being deposed in July, Lady Jane remained at the Tower. But it was now her prison, not her palace.

Jane and her husband Guildford were tried for high treason in November 1553. Mary I was merciful and granted them a reprieve, allowing the couple to remain as high-status prisoners in the Tower.

It is thought Jane was held in No 5 Tower Green, while the Duke of Northumberland and four of his sons, including Guildford, were imprisoned in the Beauchamp Tower.

Jane had some comforts, she was attended by three gentlewomen and a manservant, and was allowed to walk freely in the Queen’s Garden at ‘convenient times’.

It is possible that husband and wife had some contact with each other.

Jane and Guildford indicted

Upon her arrival in London on 3 August, Mary I immediately released the Catholics imprisoned by her father. On 12 August Jane and Guildford were indicted and on 22 August, the Duke of Northumberland was executed at Tower Hill.

Of her father-in-law, Jane supposedly said: ‘He hath brought me and our stock in most miserable calamity and misery by his exceeding ambition.’

In November the young couple was tried and convicted of treason at the Guild Hall. They were charged with high treason and sentenced to death.

However, the Queen doubted Jane's guilt and said her conscience would not permit her to have her cousin put to death. That all changed in 1554.

Rebellion against Mary I

The Queen’s staunch Catholicism and her plans to marry the hated Philip II of Spain had made her deeply unpopular. A series of uprisings followed, including the Protestant Wyatt’s Rebellion in 1554.

The conspirators didn’t intend to bring Jane back to the throne, but Jane's father was involved in the plot, and put Jane and her husband in a difficult situation. Jane’s existence became more of a threat to Mary, who could not afford to let her live.

Did you know?

During her time imprisoned, Jane Grey spent much of her time studying the Bible.

Image: Trial of Lady Jane Grey by John Faed, painted in 1832 at the age of 13. © Dumfries and Galloway Council, Kirkcudbright Galleries

Jane and Guildford are sentenced to death

Mary offered to spare their lives if they converted to the Catholic faith. Always pious, Jane was by now a passionately devout Protestant. They both refused.

With reluctance, Queen Mary I accepted the Privy Council’s advice and ordered Jane and Guildford’s execution.

Jane refused Guildford’s request to meet one last time as she felt it would cause less ‘misery and pain’ if they waited to ‘meet shortly elsewhere, and live bound by indissoluble ties.’

Guildford Dudley is Executed

On 12 February 1554, at around 10am, Guildford was taken to Tower Hill, where a crowd was waiting to watch him lose his head.

From her window, Lady Jane saw his headless body being carried back to the chapel, and is said to have exclaimed: ‘Oh, Guildford, Guildford!’

Jane's Last Moments imagined

Jane's fate has prompted many artists to create their own interpretations of her final moments. One of the most striking depictions is Hendrik Jacobus Scholten's The Last Moments of Lady Jane Grey, which was created in the 19th century.

View this painting in high definition and learn more about its contents in this Gigapixel image.

Scholten has placed Jane in an imagined Tower of London cell, despondently contemplating the news of her fate, while her attendants collapse in desolation. In reality, Jane was probably held in the relatively comfortable housing of the Tower officials around Tower Green, a form of house arrest, with four servants and access to the gardens.

Image: The Last Moments of Lady Jane Grey by Hendrik Jacobus Scholten. © Historic Royal Palaces.

'I am come hither to die': Jane Grey's Final Words

As a woman of high-status Jane was granted a private execution within the Tower grounds an hour after her husband, on 12 February 1554. Dressed in black, the young woman remained calm as she walked to the scaffold on Tower Green.

Jane's final words were dignified, among them: ‘Good people, I am come hither to die, and by a law I am condemned to the same; the fact indeed against the Queen’s Highness was unlawful and the consenting thereunto by me…I do wash my hands thereof in innocency before the face of God and the face of you good Christian people this day.’

Image: The Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula at the Tower of London. © Historic Royal Palaces

The execution of Lady Jane Grey

On the scaffold, Jane read Psalm 51 in her prayer book. She then gave her gloves and handkerchief to one of her ladies, and the prayer book to the Lieutenant of the Tower. She removed her gown, headdress and collar and handed them to her ladies.

'Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit'

Jane asked the executioner to 'despatch her quickly' and tied a blindfold around her eyes. But as she groped blindly for the block, panic overcame her and she cried 'What shall I do? Where is it?'

Someone stepped in to help, and Jane laid her head on the block.

As she spoke her last words: ‘Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit’, the axe fell. Jane was just 17 years old.

Buried in the Tower

Jane Grey was buried beneath the altar of the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London.

Lying nearby were two other Tudor queens, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard.

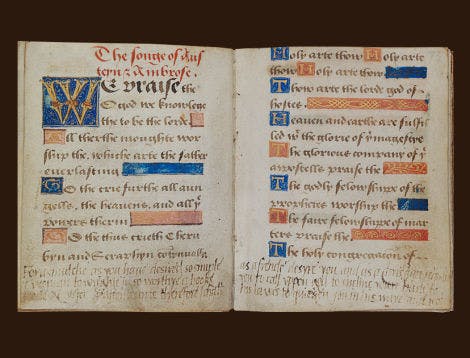

Lady Jane Grey's prayer book with her handwritten inscription to Sir John Bridges, Lieutenant of the Tower, © British Library Board, Harley 2342, ff.74v-75

'Forasmutche as you have desired so simple a woman to wrighte in so worthye a booke (good) mayster lieutenaunte therefore I shall as a frende desyre you and as a christian require you to call uppon god to encline youre harte to his lawes to quicken you in his waye and not to take the worde of trewthe utterlye oute of youre mouthe'.

Image: The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (detail), by Paul Delaroche, © National Gallery London 2017

A Protestant martyr

After Mary I’s unsuccessful reign, Lady Jane Grey became known as a Protestant martyr, while in the 19th century she was seen as an innocent victim, as imagined in Paul Delaroche’s dramatic painting from 1833.

The artist has imagined Jane in a gloomy Tower cell rather than out on the scaffold. Her white dress and the focus of light help to reinforce her vulnerable position.

Image: 'Jane' inscription carved into a wall of the upper chamber of the Beauchamp Tower at the Tower of London. © Historic Royal Palaces

Lady Jane Grey's legacy at the Tower

Fascinating traces of Lady Jane Grey's short-lived reign survive and can be seen at the Tower of London today.

In the Beauchamp Tower, to the right of the large fireplace, at about head height there is an elaborately carved coat of arms cut deeply into the wall. This is the badge of the Dudley family, probably made by Guildford or his brother Robert.

Across from the fireplace, there is another graffiti, low down at about knee-height. It reads ‘IANE’ which stands for ‘Jane.’

The story of Lady Jane Grey – of a very young girl caught in the political conflicts of her time – has fascinated audiences over the centuries.

Today, researchers are challenging some of these depictions, trying to re-interpret her story.

Was she a martyr, an innocent victim or a more complex character, the product of Tudor ambitions including her own?

With so little surviving evidence, perhaps we will never know.

Browse more history and stories

Mary I

The true story behind the ‘bloody’ Tudor queen

Edward VI

The real story of Henry VIII’s 'precious jewel' and only son

The Tower of London as a prison

The Tower is known as an infamous prison, but it wasn't built to be one

Explore what's on

- Things to see

Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula

The parish church of the Tower of London holds regular religious services throughout the year.

-

Currently closed until the end of March 2026.

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Tower Green and Scaffold site

Walk in the footsteps of those condemned to execution at the Tower of London on Tower Green and the Scaffold Site.

- Open

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Tower Hill Execution Memorial

Complete your visit to the Tower of London at the Tower Hill Memorial, in what is now Trinity Gardens. Here, an estimated 125 people were executed– including many prisoners of the Tower.

- Daily

- Tower of London

- Free

Shop online

Shop Six Wives of Henry VIII

'Divorced, Beheaded, Died: Divorced, Beheaded, Survived' - this best selling range is as colourful as it is informative.

From £15

Shop Kings & Queens of England

Discover our informative and best selling range, inspired by the incredible history of the Kings and Queens of England.

From £4.99

Tower of London Navy Raven Sweatshirt

Inspired by the infamous ravens of the Tower of London, this sweatshirt will keep you warm on those chilly days.

£38.00