The Indian Princess who fought for women’s rights

Princess Sophia Duleep Singh is best known as a suffragette, the daughter of deposed Maharajah Duleep Singh, and goddaughter of Queen Victoria. She used her wealth, her position in society and her strength of character to fight for women’s rights.

Sophia's campaigning attracted the attention of both the press and the government. Her tireless activities ranged from participating in landmark historical events such as 'Black Friday', to routinely selling copies of The Suffragette newspaper outside Hampton Court Palace.

Sophia's philanthropy extended far beyond women's rights, and she supported many individuals and causes, particularly those affecting Indians wherever she encountered them. Like her sister, Catherine Duleep Singh, Sophia’s life was truly dedicated to the fight for equality and the support of others.

Header image: Sophia in 1930. © Peter Bance

Image: Sophia Duleep Singh as a baby with her mother, Maharani Bamba. © Peter Bance

A royal heritage

Sophia Duleep Singh’s family tree

Sophia Jindan Alexandrovna Duleep Singh was born on 8 August 1876, the daughter of Maharajah Duleep Singh and Bamba Müller. Maharani Bamba was the illegitimate daughter of a wealthy German banker and an enslaved Abyssinian (Ethiopian) woman named Sofia.

Sophia was the granddaughter of Ranjit Singh, the Maharajah of the Punjab in the north-west of the Indian Subcontinent. After the death of Ranjit Singh and the assassination of three of his successors, Sophia's father Duleep Singh (aged 5) became Maharajah in 1843. Sophia’s grandmother, Jind Kaur became Regent.

Sophia’s parents met in Egypt, during one of her father’s trips back to India. The couple married in 1864 and would go on to have seven children, of whom Sophia was one of the youngest.

Sophia's names show a truly international and remarkable family history:

- Sophia, after her Ethiopian maternal grandmother;

- Jindan, after her paternal grandmother, Maharani Jind Kaur;

- Alexandrovna, after her godmother Queen (Alexandrina) Victoria.

Image: Maharani Jind Kaur, (1817 - 1863), also popularly known as Rani Jindan, grandmother of Sophia Duleep Singh. She was the youngest wife of Maharajah Ranjit Singh and the mother of Sophia's father, Maharajah Duleep Singh. History / Topfoto

How did Sophia and her family come to live in England?

After the Anglo Sikh Wars, the British controlled the Punjab and separated the 10-year-old from his mother, Jind Kaur, who was imprisoned and exiled. Duleep Singh was raised by the Scottish Surgeon, Sir John Login and his family, and kept away from his mother whom the British considered a threat and a bad influence. He was given a residence in Fatehgarh, in the north-west of the Punjab.

In 1854, Duleep Singh expressed a wish to visit England. He met Queen Victoria who was captivated by the young Maharajah, and recognised him as a fellow royal.

The events of the 1857 Indian Rebellion meant that Duleep Singh would remain in England, not least because his residence in Fatehgarh in India was destroyed.

The Queen formed a lasting and genuine, if fundamentally unequal, relationship with Duleep Singh and his family. She was godmother to Duleep Singh’s eldest son Victor and Princess Sophia.

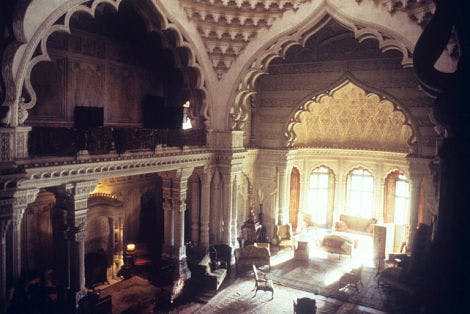

Image: The interior of Elvedon Hall, Sophia's childhood home. PA Photos / TopFoto

Sophia’s early life at Elveden Hall

Sophia's early childhood was spent in Elveden Hall in Suffolk, which her father purchased in 1863. The Elveden estate provided the family with all the pastimes expected by the English aristocracy, particularly riding and shooting.

The house itself was rebuilt by her father with an Italianate exterior and palatial Mughal interior, full of rich textiles and furnishings. It must have been a truly wondrous place to be a child. Outside, exotic animals and birds roamed the gardens including golden pheasants, parrots, and peacocks.

The great trees about the house were full of conscious parrots and other birds, and a cockatoo in shouts of laughter at the extreme top of one was very comical; he flew down and nestled affectionately in the arms of an Indian servant.

L’Aigole Cole, a visitor to Elveden in 1872

Image: Maharajah Duleep Singh in 1880. © Peter Bance

Duleep Singh attempts to return to India

Maharajah Duleep Singh lived on a pension of £25,000 a year from the India office, which he was granted provided he 'remain obedient to the British Government'. Although this was a huge sum of money, it was a fraction of what he was owed under the original treaties at the end of the Anglo Sikh Wars.

The Maharajah poured much of his income into the purchase, expansion and running costs of Elveden Hall. But by 1886, his debts had risen, and the India Office forced him to sell it.

In desperation, Sophia’s father took his family and attempted to return to India to claim what he was owed. They got as far as Aden (a city in Yemen) before he was arrested. Determined, he eventually put his wife and children on a ship back to England. He stayed in Aden to continue his campaign, and moved to France to live with his second wife.

Duleep Singh never returned to his family. But worse was to come for Sophia and her siblings.

The death of Bamba Müller

After Duleep Singh left and Elveden was sold, Maharani Bamba and the children were effectively homeless and penniless. Maharani Bamba struggled to cope with her husband’s abandonment, overcome by despair and grief.

The India Office intervened at the request of the palace, finding Bamba and the children a home in London. Arthur Craigie Oliphant and his family were put in charge of the children’s education. Suitable governesses were found to care for Sophia, her sisters and little brother Albert Edward.

In 1887, Sophia contracted typhoid fever. Her desperate mother refused to leave her bedside, even as her own condition worsened. This would be the last time Sophia would see her mother.

On 18 September 1887, Maharani Bamba Duleep Singh was found dead next to her sleeping daughter, having collapsed and slipped into a coma. She was buried in Thetford, next to Elveden Hall.

The Last Princesses of Punjab

A new exhibition at Kensington Palace

Explore the extraordinary lives of the Duleep Singh sisters and their rich and complex heritage at Kensington Palace from 26 March 2026.

Sophia’s education in Brighton

After the death of their mother, the children first lived in the Oliphant family home in Folkestone, and then in their Brighton home.

Sophia attended a nearby girls' day school in Brighton for four years. She later attended lectures at the London School of Economics, and finished her education on a six-month tour with her sisters, staying in Holland, Germany, Greece, Italy, and Egypt.

‘He is a hard worker and most excellent boy’

The death of Sophia’s beloved brother Edward

Sophia was deeply fond of her youngest brother, Albert Edward (called Edward). Sophia affectionately called him ‘Eddie’, and he called her ‘Sophy’. He was bright and excelled at boarding school; the warden described him as a ‘hard worker and most excellent boy’.

Edward wrote many letters to his big sister Sophia, updating her with his life and asking her to replenish his supplies. But he also reported his frequent colds.

Image: (Left to right) Bamba, Edward, Catherine and Sophia in 1889. © Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Dear Sophy, I and the chap I sleep with are not going to church because we have got colds[,] my cold never went and last Wednesday I got another cold.

Edward, writing to Sophia from boarding school

In January 1892, Edward contracted pneumonia. He was sent home from boarding school, and by April his condition had worsened.

Sophia’s father was summoned from Paris in April 1893 to see his dying son. But, still sick himself, he left after only a few days. A week later, aged just 13, Albert Edward died. He was buried next to his mother, near his childhood home of Elveden.

Six months later, Duleep Singh, the last Maharajah of the Sikh Empire, died in Paris in October 1893.

In the space of just five years, Sophia had lost her mother, her little brother and her father.

Image: Hampton Court Palace in the early 20th century. Sophia regularly walked her dogs in the palace grounds while she lived at Faraday House. © Historic Royal Palaces

Princess Sophia at Hampton Court Palace

Like her sisters, Sophia inherited the sizeable sum of £23,000 from her father. This was arguably a mere fraction of the wealth they could have expected from their patrimony. However, it meant that the women were independently wealthy, leaving them free to pursue their own interests.

In 1896, Queen Victoria gave Princess Sophia Faraday House, then part of the Hampton Court Estate, as a grace and favour residence plus £200 a year to maintain it.

While not the palatial surroundings her birth might have afforded her, Faraday House at least gave her the security of a home and a place to entertain.

Image: Photograph of Sophia with her horse and dogs. © Peter Bance

Sophia's passions and pastimes

Sophia had a real zest for life and many passions. She was sporty, playing hockey and riding and cycling frequently. Cycling was still becoming an ‘acceptable’ pastime for women, and Sophia’s love of cycling was covered in the press. She loved to travel and was energetic on the aristocratic social scene.

Sophia was a keen animal lover, and kept parrots and tortoises at Faraday House; her sisters Catherine and Bamba despaired. But her real love was dogs.

Since her early years spent around the hounds at Elveden, Sophia had adored dogs, and even became a leading breeder and trainer. She especially loved Pomeranians and Borzoi hounds. She took Jo, her beloved Pomeranian with her when she travelled to India in 1906.

Sophia was often seen walking her dogs around the grounds of Hampton Court Palace, including through the famous Hampton Court Maze.

Sophia's other hobbies included photography and music. At Faraday House she kept all sorts of instruments and sheet music, and was particularly fond of Liszt, Schübert and Ravel.

Sophia loved fashion, buying her clothes and accessories from the finest fashion houses of London and Paris. Sophia's older sisters often warned her not to be so decadent in her purchases. This didn't stop her dressing her servants in fine burgundy uniforms, the men resplendent in gold embroidered waistcoats.

Did you know?

Sophia bought a Steinway grand piano costing £136, about a quarter of her annual budget.

Image: Photograph of Sophia (on the right) with her sisters Bamba and Catherine. © Peter Bance

Travel to India

Sophia travelled twice to India with her sister Bamba, in 1907 and 1924. The Princesses’ second visit to Kashmir, Lahore, Amritsar and Murree was emotional and nearly caused problems for the local authorities. In Lahore, the crowds were excited to see them, resplendent in saris and traditional jewels. They shouted, ‘The Princesses are here, the daughters of Maharajah Duleep Singh,’ and, ‘We are with you, we will give you the world.’ In the end, the police dispersed the crowd.

Sophia had both pride and sympathy for the Indian people, writing in one letter, 'I was delighted to see the house of my ancestors, but oh dear how primitive it all is.'

A friend to many

Sophia's support for the Indian community in London

Princess Sophia supported Indians, particularly women, throughout her life. She formed close ties with the Sikh community in London, visiting the Sikh temple at Shepherd’s Bush regularly. She frequently attended functions organised by the India Office, including receptions for distinguished Indian visitors.

Sophia supported the Indian Women’s Education Association, volunteering at their stall at Claridges in 1921, arranged by the Conservative Women’s Reform Movement.

Like her father, Sophia helped Indian Seamen and sailors – known as Lascars – stranded in London. She promoted the Lascars’ plight among her wealthy friends, eventually raising enough money to helped build a safe haven called the Lascars Club.

Supporting her family

Sophia also paid for the education of one of her cousins, Gurdit Singh, in India.

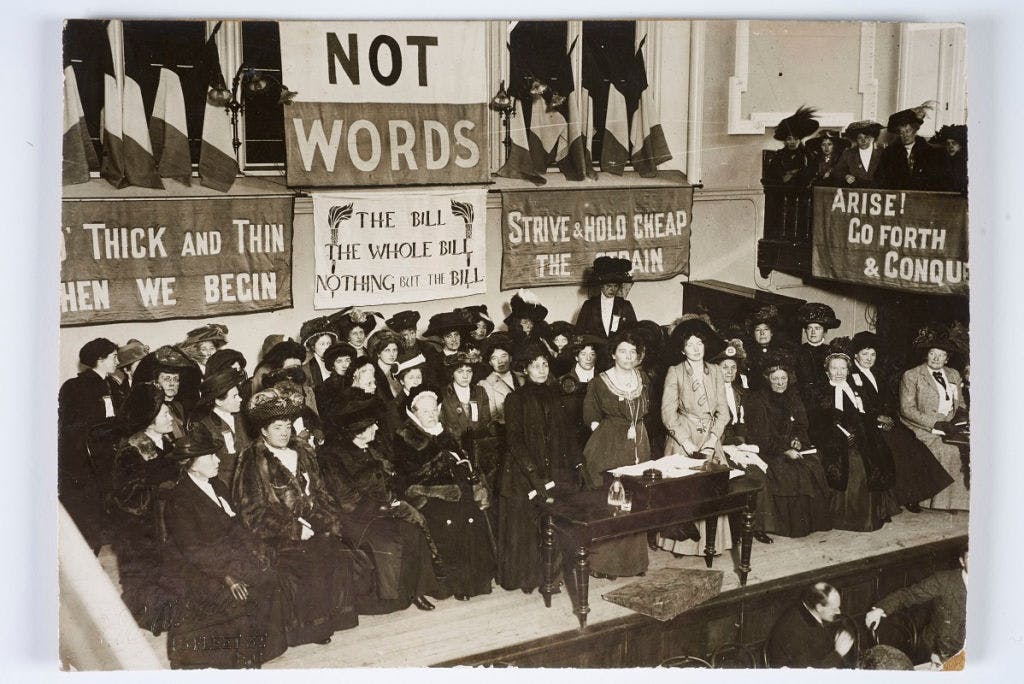

Sophia Duleep Singh, the suffragette

Sophia was a prominent and active ‘suffragette’: a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She was often seen selling The Suffragette newspaper at her pitch outside Hampton Court Palace, an activity that even the King tried to intervene in.

Indeed, much of the information we have about Sophia's activities come from The Suffragette and Votes for Women newspapers.

In one dramatic story, Sophia even petitioned Prime Minister Asquith in person at Downing Street, brandishing a ‘Give women the vote’ banner at him. To avoid embarrassment for the British government, she was released without charge.

From her home at Hampton Court, Sophia participated in the mass boycott of the 1911 census. Along with others who could afford to risk the fine, she spoiled the census form sent to record the whereabouts of every citizen in the country – on the basis that if women were allowed the vote, they refused to be counted as citizens.

Did you know?

‘Suffragette’ was originally coined in 1906 by Charles E Hands of the Daily Mail, as an insult for WSPU members. The WSPU reclaimed it, changing the pronunciation to mean ‘we are going to suffra-get-the-vote’.

Image: Sophia selling subscriptions to the Suffragette newspaper on her pitch outside Hampton Court Palace. © Museum of London

No Vote, No Census. As women do not count, they refuse to be counted. I have a conscientious objection to filling up this form.

Sophia Duleep Singh on her census return in 1911

Black Friday

On 18 November 1910 (now known as ‘Black Friday’) Sophia was among more than 300 suffragettes who marched from Caxton Hall to Parliament Square and demanded to see the Prime Minister.

The Prime Minister declined, but Sophia and her fellow protestors refused to disperse. Although he would later deny it, Home Secretary Winston Churchill was blamed by the Metropolitan Police Commissioner for encouraging the violence that followed.

Over six hours, 200 women were physically and sexually assaulted by police. Two women would later die from their injuries.

This experience must have been terrifying, but Sophia stood her ground. When violence erupted, she rescued a woman from a police officer, who was treating her extremely roughly. Sophia pursued the officer until she discovered his identification number (V700), to make a formal complaint.

The policeman was unnecessarily and brutally rough and Princess Sophia hopes he will be suitably punished.

Sophia Duleep Singh, in her complaint about a police officer on Black Friday

Over 100 protesters were arrested on Black Friday, but all were released the next day without charge on Churchill's orders. The Home Secretary refused an official enquiry.

No vote, no tax!

Sophia Duleep Singh and tax resistance

Sophia is even better known as a member of the Women’s Tax Reform League (WTRL), which campaigned on the principal – 'No Vote, No tax!'.

In May 1911 Sophia was summoned to court and fined £3 for keeping a man-servant, five dogs and a carriage without licence. In 1913 she was summoned again to answer for keeping dogs and a carriage without a licence.

The Princess protested that taxation without representation was tyranny: ‘When the women of England are enfranchised and the state acknowledges me as a citizen I shall, of course, pay my share willingly towards its upkeep.’

Sophia was fined £12 10s. with costs. When she refused to pay, some of her jewels were confiscated and auctioned – only to be bought back by other tax resistors, to much applause.

Did you know?

The WTRL refused to pay a variety of taxes, insurances and license fees, including income tax, property tax, dog tax, and even servant insurance.

Image: Sophia during her time as a nurse. © Peter Bance

Wartime

Sophia during the First World War, and the Red Cross

When the First World War broke out in 1914, the WSPU and WTRL temporarily ceased activity. Ever the philanthropist, Princess Sophia once again used her time and celebrity to support the war effort.

In 1915, Sophia was part of the 10,000-strong Women's War Work Procession led by Emmeline Pankhurst, and joined the Voluntary Auxillary Detachment Service as a nurse. For two years, she worked 37 hours a week in Isleworth Hospital – a total of 1,500 hours of unpaid work.

In her spare time, the Princess visited troops at Brighton Pavilion and other hospitals for Indian soldiers. Many soldiers were amazed to see the Princess – the granddaughter of the famed Maharajah Ranjit Singh – in the flesh. She gifted mementoes of signed photographs and little ivory mirrors.

I have had an interview with the grand daughters of King Ranjit Singh. They gave me a memento, a pair of socks. They come to see Sikhs from time to time. To this day they speak Punjabi plainly, and I have sent the socks home by the hand of a friend as a memento.

Halvadar Jass Singh whilst in hospital, to Bir Singh, 23rd Pioneers

In 1916, as part of the ‘Our Day’ celebrations marking the anniversary of the British Red Cross, Sophia joined other Indian women to raise money selling Indian flags at Dewar House in Haymarket.

In 1918, the YMCA War Emergency Committee, of which Sophia was Honourable Secretary, organised a flag day in London and later 'India Day' for the support of India's soldiers and Labour Corps. The latter event provided 50,000 huts for the comfort of Indian soldiers. To promote this day of fundraising, she appeared in many different newspapers, appealing to the public not to forget the men who in her words ‘nobly did their part’.

I am confident that Britons will take the opportunity to show in a substantial way, their appreciation of the splendid work my countrymen have been doing.

Sophia Duleep Singh, writing in the Ladies Pictorial, 21 September 1918

When Indian Soldiers were encamped at Hampton Court, Sophia made every effort to visit them and to invite as many as she could to Faraday House. A keen photographer, she took a photograph of every soldier who visited. She created a huge album to remember their visit, making notes of the names of all soldiers she encountered, and keeping mementoes of the encampment.

Equality at last?

Sophia’s suffrage legacy

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act granted the vote to some women over 30 in Britain. This was a significant step towards equality, but it would be another 10 years before women were finally given the vote on the same terms as men.

Even after this point, Catherine and Sophia continued to attend dinners and gatherings of the movement. Sophia was a member of the Suffragette Fellowship, which aimed to preserve ‘the memory of the pioneers and outstanding events connected with women's emancipation… and thus keep alive the suffragette spirit.’

'The refugees were coming and going'

Sophia and Catherine take in refugees during the Second World War

During the Second World War, Sophia moved to Rathenrea, a house next to Catherine in Buckinghamshire. Keen to use their space outside London to help the war effort, the Princesses took in evacuees from west London; siblings John, Michael and Shirley Sarbutt arrived at Rathenrea in September 1939.

The children remembered the stay fondly, recalling oriental ornaments, ample food and a parrot called Akbar. During air raids they would squeeze into the air-raid shelter surrounded by the Princesses' dogs.

Princess Sophia also assisted her sister Catherine in accommodating Jewish refugees at Faraday House. These included Alexander Poliarnoff who was a violinist, and the Chopin family who stayed at Faraday House for four months.

My Mother, Father and two sisters were looking after the house at Faraday and various refugees turned up. The refugees were coming and going.

Mike Turner, whose parents worked for Princess Sophia

Image: Sophia holding her goddaughter, Alexdrovna (Drovna) Oxley. © Peter Bance Collection

Drovna

'[Sophia] would have made a lovely mum'

The evacuees from London were not the only children that Sophia doted on in her later life. Her adored goddaughter, Catherine Alexandrovna Oxley (called Drovna) was the daughter of her housekeeper Janet (‘Bosie’), and her chauffeur John. Drovna lived at Faraday House from birth until Princess Sophia died when she was 9 years old. She was a favourite of the Princess and had a room next to her.

Drovna remembers the Princess well. She often took her to see the Hampton Court Gardens, including a special visit to see the black tulips in 1944; the tulips were a new breed which had only been introduced three years before. Sophia also took Drovna to Hyde Park to give food to the homeless.

Fittingly to the protégé of the famous suffragette Princess Sophia, Drovna’s strongest memory is being made to go on her knees and promise always to vote.

Image: Sophia in 1930. © Peter Bance

The death of a princess

Sophia Duleep Singh dies

Princess Sophia Duleep Singh died in her sleep on 22 August 1948. On her instructions, a full band played Wagner's 'Funeral March' at her cremation. Her ashes were taken to India for burial.

Sophia Duleep Singh's legacy

Although not a fan of public speaking, and often anxious not to draw attention away from fellow suffragettes, Sophia's celebrity was ultimately an important asset for the suffragette movement.

Even after women won the vote, this was not the end of the matter for Princess Sophia who continued to campaign for equality all her life.

Passion for the cause

In the 1934 edition of Women’s Who’s Who, Sophia listed Advancement of Women as her only interest.

Suggested reading

For more information on Sophia Duleep Singh and her family, please refer to the following books and websites:

- Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary by Anita Anand (London, 2015)

- Sovereign, Squire & Rebel: Maharajah Duleep Singh by Peter Bance (London, 2009) and accompanying website.

- Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History by Rozina Visram (London, 2002)

Watch Sophia Duleep Singh: Suffragette princess

Anita Anand explores the extraordinary life of Princess Sophia Duleep Singh in this mini-documentary.

Watch on YouTubeThis content is hosted on YouTube

This content may be using cookies and other technologies for which we need your consent before loading. To view the content, you need to enable cookies for "Targeting Cookies & Other Technologies".

Manage CookiesVideo transcript

Follow along with an interactive transcript of this video on YouTube. A link to open the transcript can be found in the description.

Browse more history and stories

Catherine Duleep Singh

The Indian Princess who became a 'guarantor' to Jewish refugees escaping Nazi Germany, and an icon for LGBTQ+ South Asian women

Duleep Singh

The last Sikh Maharaja of the Punjab and former owner of the Koh-i-Noor diamond

The Indian Army at Hampton Court Palace in 1919

A forgotten story

Explore what's on

- Exhibition

- Things to see

The Indian Army at the Palace

Explore the forgotten story of Indian Army soldiers who camped at Hampton Court Palace in the early 20th century, through a new exhibition of previously unseen objects, photographs, film and personal stories.

-

Closed

- Hampton Court Palace

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Hampton Court Gardens

Take time to explore and relax in these world-renowned gardens and find our free entry Garden Open Days dates.

- Open

- In line with palace opening hours

- Hampton Court Palace

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

The Crown Jewels

Discover the dazzling history of the Crown Jewels in the spectacular Crown Jewels exhibition.

-

Open

- Allow one hour

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)