Secrets of Henry VIII's Whitehall: The Archaeology of a Lost Palace

Date: 17 August 2023

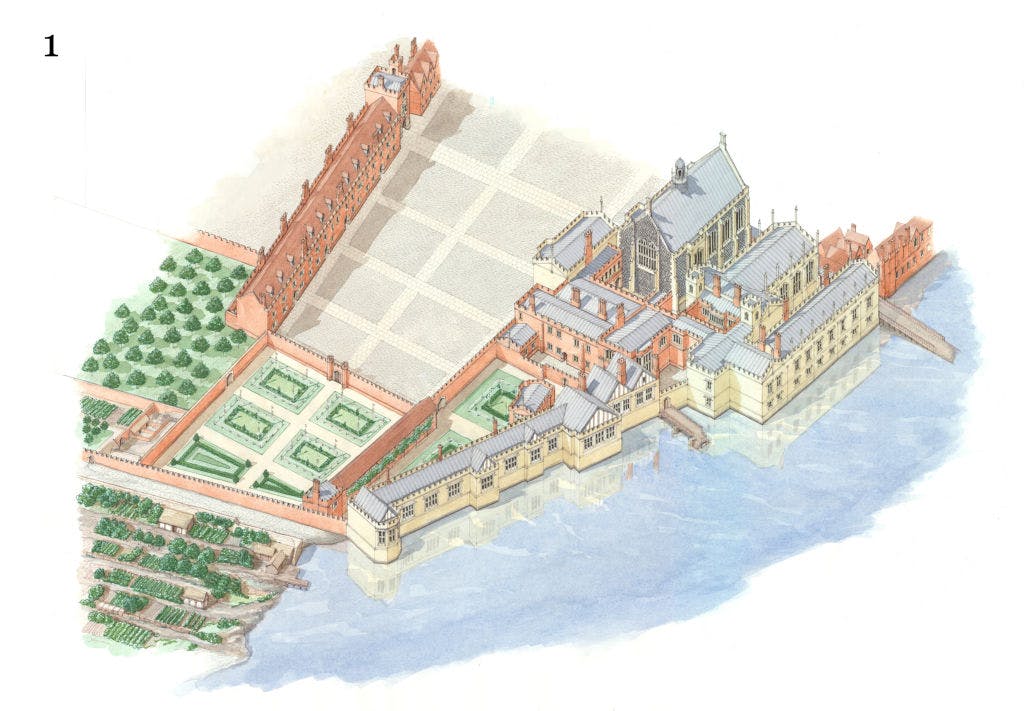

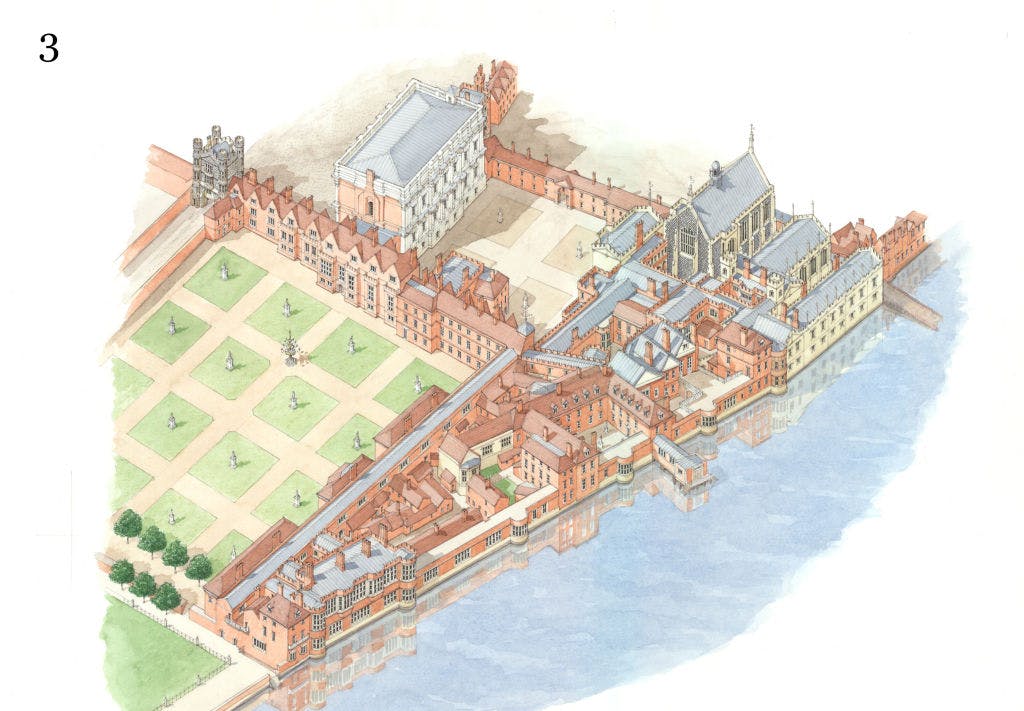

On January 4 1698 a catastrophic fire broke out in Whitehall Palace. The Banqueting House, arguably the most architecturally and artistically important part of the palace was saved and can still be seen today, but the rest of Whitehall Palace was razed to the ground. More than 300 years after its destruction, archaeological excavation and scientific analysis continue to uncover the lost stories and secrets of this once elaborate palace.

Whitehall Palace was once Henry VIII's London residence. Today, the area has become the location of the departmental centre of government in the United Kingdom. Beneath these governmental buildings though, much of the palace survives – in some cases only centimetres beneath your feet - making the area surrounding the Banqueting House one of the most archaeologically important, and delicate, in the country.

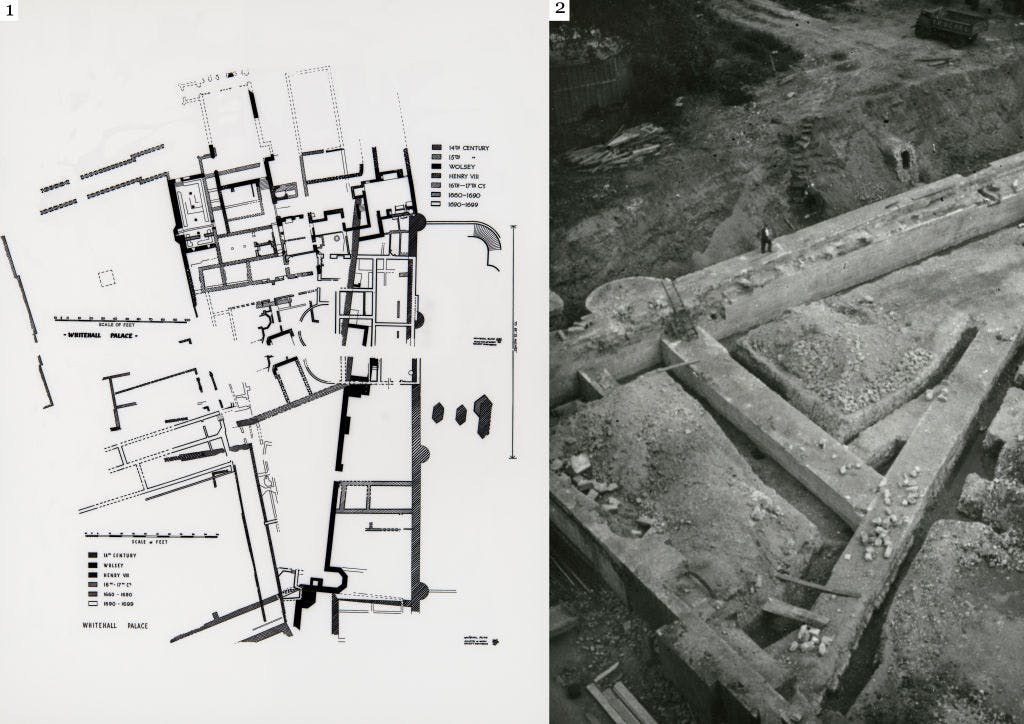

During the construction of the Ministry of Defence building in the mid-20th century, vast swathes of Henry VIII's lost palace were uncovered and recorded. This work forms the foundation of our understanding of the palace and a section of Henry’s wine cellar even remains preserved within the new building.

More recently, between 2014 and 2021, archaeologists from Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), LP-Archaeology and Pre-Construct Archaeology have each uncovered some of this unique heritage to the north and east of the Banqueting House – giving us a rare glimpse of Henry VIII’s magnificent palace.

The first of these exercises in 2014, a watching brief on excavations to the east of the Banqueting House, identified a brick surface, probably a floor, at a depth of 1 metre immediately to the rear of the building. This surface was dated to between 1450 and 1650 by brick typology – an analysis of the form and fabric of bricks which change gradually through time. No conclusion has been reached about the origin of this surface, but research suggests it could relate to several different buildings.

It may be a surviving feature of courtier lodgings built before 1547 or even from banqueting houses built in 1581 and 1606-9 during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, or perhaps it represents a lost part of the current Banqueting House. Although we are unable to say exactly which building it relates to, proper recording means that in the future archaeologists, historians and curators can combine new findings in order to create a more complete picture of the lost palace.

Further excavations undertaken in September and October 2021 uncovered more substantial remains beneath Horse Guards Avenue. Most of these are related to different phases of the original landward gate of the palace known as Court Gate - and some of these may even pre-date Henry VIII’s acquisition of the palace from Cardinal Wolsey.

This gate was situated opposite the current position of the Horse Guards between the Banqueting House and the Old War Office. Opening into the principal courtyard of Whitehall Palace, it acted as a physical link between the two powerhouses of the capital, the mercantile and political power of London with the monarchical power of the royal palace.

It’s important to remember that Whitehall Palace was not a static structure. It was a physical manifestation of power and framed the perception of the monarch. Due to this, the palace went through numerous periods of demolition, alteration, and rebuilding in order to follow new fashions and maintain its stability for various Tudor and Stuart monarchs, almost all of which were in red brick! Court Gate was no exception at least four phases of its construction were discovered during these excavations.

Trying to see the difference between these deposits can sometimes be difficult. Historic plans, account books and images may give us an indication of when, where, and how a structure was built, however, these are very rarely precise. Similarly, brick typologies may give an indication of how old a structure is, but a feature can also appear older or younger, through later alteration or the re-use of historic material.

It is the skillful use of each of these sources together with the re-assessment of historic excavations which enables a collection of red bricks to become a part of the story of Whitehall palace - but this is rarely certain. The true value of these exercises is in the creation of a ‘permanent record’ which means that each of these excavations, although small, can be re-assessed in the future as more evidence comes to light and the story of Whitehall can become clearer and more detailed over time.

Banqueting House, the remaining part of the destroyed Whitehall Palace, today often seems lost against the monolithic governmental buildings of Whitehall. But it is the second oldest Palladian building in England built by renowned architect Inigo Jones and holds the only in-situ painted ceiling by Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens.

Alfred R J Hawkins BA(Hons) MA MCIfA

Assistant Curator of Historic Buildings

Historic Royal Palaces

Further Reading

- Fiona Keith-Lucas, BQH04: Archaeological Building Recording of the North Annexe Cellar, Banqueting House, Whitehall Palace, (Historic Royal Palaces, 2015).

- Greg Laban, BQH03: The Banqueting House Whitehall, Archaeological Watching Brief Report, (MOLA, 2017).

- Alfred Hawkins, BQH06: Historic Building Record, The Banqueting House, James Wyatt’s Grand Staircase Ceiling, (Historic Royal Palaces, 2018).

- Stella Sudekum, BQH07: Archaeological Watching Brief Report, Banqueting House, Whitehall, (LP-Archaeology, 2021).

Forthcoming publications

- James Langthorne, ‘Whitehall Palace’s Court Gate and Gower/Carrington House as Revealed in Archaeological Investigations in Horse Guards Avenue’, London Archaeologist.

Finalised reports can be made available upon request via Historic Royal Palaces (curators@hrp.org.uk) or the Historic England Greater London Historic Environment Record (GLHER) (glher@historicengland.org.uk)

More from our blog

How did Henry VIII and his family say 'I do'?

09 February 2026

Tracy Borman explores some notable Tudor royal weddings and their traditions, from private nighttime ceremonies to grand celebrations.

Christmas in the Tudor royal court

22 December 2025

Tracy Borman heads back to the courts of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I for a Christmas like no other.