James VI and I was the first Stuart king of England. Anne of Denmark was his queen.

James I and IV became King of Scotland in 1567, aged just 13 months, following the abdication of his mother, Mary Queen of Scots. He succeeded Elizabeth I as James I, King of England in 1603, thereby unifying the thrones of England and Scotland.

At this time, James and his wife Anne had three young children: Henry, Elizabeth, and Charles (later Charles I). The arrival of the generous, scholarly James, his cultured wife and his young family was eagerly anticipated at the English court. Elizabeth never married, so James, Anne and their children were the first royal family in England for 44 years.

James I and IV was a religious reformer, obsessed with witches, a keen patron of architecture and the arts, and an early anti-smoking campaigner. He built the magnificent Banqueting House, which still stands in Whitehall, London.

Anne of Denmark was assertive and independent, a dynamic patron of the arts who constructed a magnificent court.

Image: James I of England and VI of Scotland, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Image: Anne of Denmark by John De Critz the Elder, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Who was Anne of Denmark?

James VI and Anne of Denmark were married in 1589, when she was just 14.

On her journey to Scotland she was marooned in Norway. James made the chivalrous decision to travel out and rescue her.

In their early life in Scotland, Anne showed an independent streak. She was not afraid to challenge her husband and manipulated political factions to achieve her own ends.

Once in England, Anne threw her energy into patronage of the arts, creating a cultural salon that attracted leading painters, writers and thinkers.

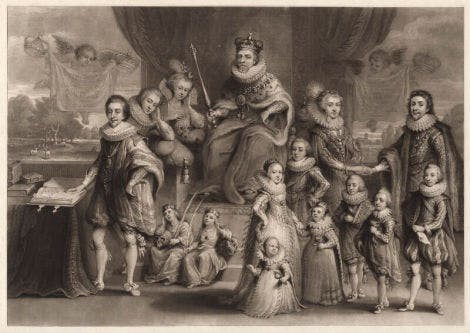

Image: James I and VI and his royal descendants. © National Portrait Gallery, London

James and Anne's unhappy family

James and Anne had five children, although only three survived infancy: Henry, Elizabeth, and Charles (later Charles I). Henry, Prince of Wales, died unexpectedly in 1612, leaving Charles as heir to the throne.

From an apparently happy and loving relationship, the King and Queen drifted apart. James’s private life was shadowed with rumours concerning his male favourites and possible lovers, notably Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset and George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham.

The King's obsessions

Alongside his religious writings James published a series of books and pamphlets on the subject of witchcraft and ancient dark magic. James I and VI's famous book Daemonologies (1597) describes the acts of demons, werewolves, and vampires and how they should be persecuted under Christian law.

His obsession with witches (who he believed acted in groups and were hell bent on murdering him) is thought to have led to hundreds of (mainly) women being put to death.

James also disliked tobacco, especially tobacco smoking. His Counterblaste to Tobacco (1606) was one of the first anti-smoking pamphlets.

Image: The Tower of London viewed from the River Thames. © Historic Royal Palaces

The King’s cruel streak

James I and James VI stayed at the Tower of London after he arrived in his new kingdom in 1603. He was the last monarch to stay at the fortress and particularly enjoyed watching the cruel animal displays there.

In the Tower Menagerie, the King had the lions' den refurbished so that visitors could look down into a semi-circular yard lined with dens and with a drinking trough at the centre. This was less out of a concern for the lions' welfare, and more for his own enjoyment. James' favourite sport was to bait the lions with vicious mastiff dogs.

Image: The Tudor apartments at Hampton Court Palace. © Historic Royal Palaces

Hampton Court and The King James Bible

Hampton Court Palace was the setting for the religious conference of 1604 which led to the King James Bible.

James passionately studied modern and ancient theology and proved to be an articulate writer on the subject. He once said if he were not King he would like to have been a 'university man'.

William Shakespeare's acting company, The King’s Men, first performed for James I and VI in the Great Hall of Hampton Court Palace.

Image: A carved stone portrait of James VI and I in the King’s House at the Tower of London. © Historic Royal Palaces

James I and VI and the Gunpowder Plot

James' mother, Mary, Queen of Scots had been a devout Catholic. So when the Protestant James I and VI became King of England, Catholics across the country hoped that he would be tolerant of their religious beliefs. But they were to be disappointed.

On the night of 4-5 November 1605, a group of plotters — including Guy Fawkes — took drastic action by attempting to assassinate James and his Parliament. The plan failed, and the plotters were put to death.

This foiled plot is now commemorated every Guy Fawkes Day on 5 November, inspired by a thanksgiving act passed by the King in 1606.

Image: Mezzotint of James I and VI and Anne of Denmark, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017. Detail used as header image.

James and Anne's new Banqueting House

Despite their differences, both James and Anne adored the masque. This was an extravagant costumed theatrical performance, blending poetry, propaganda, music and dance. New to power, the King and Queen wanted to commission a suitable venue at Whitehall Palace.

The Elizabethan banqueting house at Whitehall had been constructed in 1581. This ageing structure was only intended to be temporary, but now needed replacing.

James commissioned a new banqueting house from architect Robert Stickells, but he was hugely disappointed with the finished building. It was used for the first masque in 1608, but in 1619 it burnt down in a fire.

The calamity gave James the chance to commission a building that properly suited his needs, and he turned to brilliant designer and friend of the Queen, Inigo Jones.

Image: The Banqueting House, the only building that survived the disastrous Whitehall Fire of 1698. © Historic Royal Palaces

Inigo Jones' builds a stunning new Banqueting House

London-born Inigo Jones was highly regarded at court as Anne’s set designer and architectural advisor. While travelling Europe as a painter, he worked for her brother, Christian IV of Denmark.

This connection likely got Jones the dream job as Anne’s masque designer and ultimately, the commission to build a new banqueting house.

When it was finished in 1622, the Banqueting House stood out for miles around. It would have been a stunning sight, in contrasting layers of honey-coloured and pinkish-brown stone. It can still be seen in Whitehall today, complete with Charles I's magnificent painted ceiling featuring James I and VI himself.

Image: Anne of Denmark. © National Portrait Gallery, London

James and Anne's separation

Anne was criticised for her frivolity – her enjoyment of garments and jewellery was at odds with James’ straightforward, logical nature.

The Queen pursued pleasure and spent extravagantly. Her masques glorified her position and she delighted in her image alongside mythological goddesses. Against a staunchly Protestant nation and King, Anne quietly converted to Catholicism. This aroused fears in how the royal children and heir would be raised.

When Anne died at Hampton Court Palace in 1619, she and the King had not shared a household in 10 years. James was superstitious of everything related to illness and death, so kept a wide berth during the Queen’s decline and funeral. However, he felt great sadness following her death and wrote melancholy verses to express his sorrow.

Image: James I and VI (1566-1625) c1620. The King's new Banqueting House can be glimpsed in the background, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

The death of James I and VI

Towards the end of his life, James was known as a slobberer and semi-incoherent speaker – his tongue was too big for his mouth. He was also known as the ‘wisest fool in Christendom’, but he was far more intelligent than his ‘fool’ tag suggests.

James I and VI died in March 1625, aged 58.

James I and VI's legacy

James was the most academically gifted monarch, being both stoic and practical. He had once hoped to bring peace to Europe but had to settle with peace between England and Scotland.

He united the thrones of Scotland and England, changing the direction of English history. As the patron of Inigo Jones’s dazzling Banqueting House, he made an important contribution to English architecture.

Perhaps his finest legacy is The King James Bible, the authorised version of the Bible in English, which was published in 1611 after the hugely influential Hampton Court Conference.

More Stuart History

George Villiers, The King's Favourite

In the ruthless world of the Stuart court, royal favour was everything. No one knew this better than George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, whose rise to power was built on the love and patronage of King James I (VI of Scotland).

Listen to the Podcast

Delve into the love life of James I and VI with our Historic Royal Palaces podcast. In this episode, Chief Historian Tracy Borman is in the Great Hall at Hampton Court Palace, joined by Gareth Russell, to discuss the subject of his latest book 'Queen James; the life and loves of Britain's first King'.

More episodesBrowse more history and stories

The story of Banqueting House

Four hundred years of history and the site of a royal execution

The execution of Charles I

Killing of a 'treasonous' King

The masque

A fabulously extravagant early 17th century court entertainment

Explore what's on

- For members

- Events

Members-Only Days at Banqueting House

Explore the Banqueting House, Whitehall on this exclusive members-only day after its temporary closure. Learn all about this iconic building and its rich history.

-

21 March, 10 April, 02 May, 28 May, 27 June

- 10:00 - 16:00 (last entry at 15:00)

- Banqueting House

- Separate ticket (advance booking required)

- Events

- Things to see

Open Days

Experience four centuries of art, architecture and history on an Open Day at Banqueting House.

-

20 March, 03 April, 01 May, 29 May and 26 June

- 10:00-16:00. Last admission 15:00.

- Banqueting House

- Separate ticket (advance booking required)

- Things to see

The Undercroft

Explore the vaulted drinking den beneath the Banqueting House, which was used by James I and VI for decadent royal parties.

- Banqueting House

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

Shop online

Charles I Dated Decoration

This exclusive decoration has been created to commemorate the reign of Charles I who ascended the throne 400 years ago.

£50.00

Shop Banqueting House

Discover our wonderful collection of gifts and souvenirs inspired by Banqueting House.

From £4.50