The formidable wife and Queen Consort of William I (‘the Conqueror’), who helped establish the Norman dynasty

Matilda of Flanders was Queen of England and the wife of William I (‘the Conqueror’), its first Norman king. Matilda’s bloodline enabled William to pursue his claim to the English throne; she could trace her descent from the kings of France, the emperors of Germany and even the Anglo-Saxon dynasty.

Matilda was the first consort in England to be crowned and formally recognised as Queen, rather than simply the king's wife.

After William took the English throne as William I, Matilda became the matriarch of the new Anglo-Norman dynasty. Building on a long medieval tradition of women playing an active part in politics, she established a model of queenship that would influence her successors for centuries. She wielded immense power in both Normandy and England – not just on behalf of her husband, but at times in direct opposition to him.

Matilda’s remarkable story is played out against one of the most transformative periods of European history.

Image: Statue of Matilda of Flanders by Carle Elshoecht (1850) in Luxembourg Garden, Paris. © FORGET Patrick / Alamy Stock Photo

A ‘highly born’ descendant of kings

Who was Matilda of Flanders?

Matilda of Flanders was born in around 1031. She was the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Flanders (which was then one of the most important principalities in Europe) and Adela, daughter of Robert II ‘the Pious’, King of France.

There are few contemporary sources for Matilda’s life, but she had a better education than most noble women at the time and a sharp intellect.

She was also politically astute, strong-willed and fiercely ambitious – qualities that would spark criticism and unease among her contemporaries. These qualities would shape the negative portrayals of her in medieval chronicles.

There is no surviving likeness of Matilda, but her appearance was widely praised by contemporaries. A Norwegian chronicler described her as ‘one of the most beautiful women that could be seen’. Her skeleton was examined in 1961 and recorded as being four feet two inches tall. This was likely a miscalculation, but she was known to be of small stature, as was her eldest son Robert ‘Curthose’ (meaning ‘short trousers’).

As the daughter of a powerful ruler, Matilda was viewed as a great prize in the international marriage market. Among her first suitors was an Anglo-Saxon lord named Brihtric. He eventually rejected the proposal, but Matilda never forgot the slight. She later had his lands confiscated and threw him into prison, where he died. Clearly, she was a force to be reckoned with – but so was her next suitor.

Did you know?

Early medieval society was dominated by men. The 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry includes 600 different men and just three women.

A violent beginning?

Matilda is betrothed to William, Duke of Normandy

The illegitimate William (then Duke of Normandy) was a fierce, accomplished warrior but never shook off the stain of bastardy. He therefore set his sights on a wife with more than enough royal blood for the both of them. The beautiful, ‘high born’ Matilda of Flanders fitted the bill.

Matilda’s father proved enthusiastic when Duke William proposed marriage to his daughter. But when Matilda heard of it, she refused to marry a ‘base-born duke’. If contemporary chronicles are to be believed, William reacted with shocking violence.

According to these sources, William rode to Flanders, dragged Matilda to the ground, rolled her in the mud and almost beat her to death ‘with his fists, heels, and spurs’. A few days later, Matilda announced that she would marry none but William, since ‘he must be a man of great courage and high daring’ to have ventured to ‘come and beat me in my own father’s palace.’

This story cannot be proven and the contemporary chronicles often included outlandish stories as a means of moralising about the events they described. It is possible that here they were seeking to prove how foolhardy it was for a woman to go against a man’s will. Whatever the truth, the couple were betrothed shortly after William’s proposal.

Image: La Trinité in Caen. © Hilke Maunder / Alamy Stock Photo

The rise of the Duke and Duchess of Normandy

Matilda of Flanders marries Duke William

In defiance of Pope Leo IX, who prohibited the match because the couple were distantly related, Matilda and William married in secret in around 1050.

The marriage proved a resounding success. As the first Duchess of Normandy in 30 years, Matilda was immensely popular, both with the people of the duchy and with her husband. One chronicler noted that her ‘fruitfulness in children excited in his [William’s] mind the tenderest regard for her’.

Matilda gave birth to at least 10 children during her marriage, including four sons to continue the Norman dynasty. A woman of keen intellect, she superintended her children’s education and ensured that her daughters were imbued with as much learning as her sons.

The growing status of this power couple on the European stage was acknowledged when, in 1059, Pope Benedict overturned the ban on their marriage. Matilda and her husband each commissioned a spectacular new abbey in Caen as a mark of their gratitude. But there was much more to come.

William becomes 'Conqueror'

The death of Edward the Confessor and the conquest of England

With her royal ancestry, Matilda of Flanders bolstered her husband’s claim to the crown of England, as well as his standing in Normandy.

According to the Bayeux Tapestry (likely commissioned by William’s brother) the old King Edward the Confessor nominated William as his heir to the throne, instead of the Saxon claimant Harold Godwinson.

The tapestry also depicts Harold surrendering his claim in favour of William’s, after being shipwrecked off the coast of Normandy in 1064 – apparently persuaded by Matilda. Even if this is true, William’s claim was far from guaranteed – the English would still have to accept a Norman king, and Harold Godwinson was a stubborn opponent.

William would need all the help he could get if he wanted the English throne, and Matilda’s ancestry and diplomacy would prove to be a vital asset.

Edward the Confessor died in January 1066, and Harold seized the English throne. William took decisive action to retaliate, at once planning to invade and take the crown by force.

At this critical moment, Matilda’s tact would again prove useful. More alive to the importance of public image than her husband, Matilda sought the Pope’s sanction for the invasion. This seems to have been granted; as a token of thanks, Matilda gave her daughter Cecilia to the abbey she had built in Caen.

Matilda also commissioned a magnificent flagship, The Mora, for her husband to sail across the Channel in September of that year.

Matilda, the new Queen of England

Matilda was in the Benedictine priory of Nôtre Dame du Pré, a small chapel that she had founded in 1060 on the banks of the river Seine near Rouen, when a messenger arrived with the news that William had vanquished Harold at the Battle of Hastings. She was now Queen of England.

This was an honour that Matilda could not possibly have hoped for when she had agreed to marry William 16 years earlier.

She joyfully proclaimed that the priory should henceforth be known as ‘Nôtre Dame de Bonnes Nouvelles’ (‘Our Lady of Good News’). She also ordered several high-profile events and services across the duchy to celebrate (and justify) her husband’s conquest.

Despite these festivities, William’s victory at Hastings was just the start of a bitter campaign to bring England fully under his control. Even his coronation on Christmas Day 1066 was a tense affair; guards were placed all around the abbey in case of rioting among the resentful Saxon citizens.

Did you know?

Although Matilda was later credited with making the Bayeux Tapestry with her ladies, this was likely commissioned by William’s half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux.

Matilda’s coronation

After remaining in Normandy as regent during the months immediately following the conquest, in 1068 Matilda set sail for her new kingdom. Her coronation – described as a ‘very rich festival’ – took place at Westminster Abbey on 11 May 1068. This was Whit Sunday, one of the most important dates in the Christian calendar.

This was a pivotal moment both for the Norman dynasty and the English monarchy. Matilda was spoken of as ‘la Royne’ by the Normans, which implied that she was a female sovereign in her own right.

Her decisive first move as a crowned queen would set the tone for the rest of her reign.

Image: King Henry I after unknown artist. Matilda gave birth to her last child, Prince Henry, in England. © National Portrait Gallery, London

A Norman heir, born on English soil

Just after her coronation, Matilda travelled 200 miles north to York, determined to give birth in England’s most rebellious region to help quell resistance.

She made it as far as Selby, 14 miles south of York, where she gave birth to her fourth son (and final child) Henry – the future Henry I. By giving birth to a male heir on English soil, Matilda had, at a stroke, achieved more towards Anglo-Norman integration than her husband had during his many hard-fought campaigns since 1066. In an age when travel was tortuously slow, uncomfortable and dangerous, this was no mean feat.

Many Saxons regarded Prince Henry as the only legitimate heir to the throne, taking precedence over his elder brothers Robert, Richard and William. According to the chronicler Orderic Vitalis, Matilda encouraged this view by making him heir to all her lands in England.

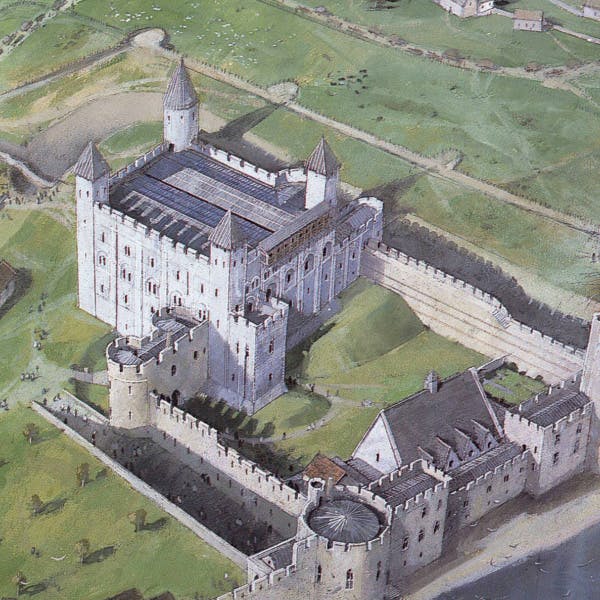

Image: The White Tower, first built by William the Conqueror. Matilda likely stayed here during her visits to London. © Historic Royal Palaces.

What type of Queen was Matilda?

Matilda recognised, as the new William I did not, that her husband needed to win his English subjects’ hearts and minds, not just their bodies. At first, the conquered Saxons were suspicious of their powerful new Queen and called her ‘the strange woman’. But Matilda gradually won them over through her gracious manner and regal bearing.

Appreciating the need for a monarch to be visible to their subjects, Matilda travelled widely within England and made regular journeys to Normandy.

She also probably made use of William's first – and most formidable – castle, the ‘Great Tower’ (later known as the White Tower) in London.

This physical manifestation of William’s new power was a palace as well as a prison, and Matilda likely stayed there during her visits to the capital. This tower still stands – now part of the Tower of London.

Matilda gave the Norman court much-needed majesty and splendour. Her husband was more at home on the battlefield than in the glittering palaces of his new kingdom; he would regularly hold court on a carpet in the forest while on campaign.

Neither did he have much patience for the elaborate ceremony and ritual that he had inherited; he once tried to stab an abbot in the hand when granting a charter.

Under Matilda’s influence, however, the Norman court became a lively cultural centre frequented by poets, artists and musicians. She commissioned luxurious new clothes for herself and William, and they ate their meals from gold and silver platters.

Matilda also introduced regular ‘crown-wearings’ to coincide with the great religious feasts such as Easter, Whitsun and Christmas. On such occasions, William and Matilda would appear richly attired in gold cloth, crowns glittering on their heads to emphasise their legitimacy as King and Queen of England.

England’s Queen soon came to wield as much authority in England as she did in Normandy. With her husband on military campaign for much of the time, she wielded royal power in both England and Normandy on his behalf.

Matilda’s name appears regularly in charters and other legal documents. She is almost always styled ‘regina’, and occasionally ‘regina Anglorum et comitissa Normannorum et Cenomannorum’ (‘Queen of England and Countess of Normandy and Maine’). For a woman’s authority to be so openly acknowledged was unprecedented in England.

‘Matilda – wealthy and powerful’

The native Saxons referred to the Queen as ‘Matilda – wealthy and powerful’. She was certainly both.

Domesday Book, the comprehensive survey of England that William commissioned in the 1080s, proves that Matilda was the greatest female landowner in the kingdom, as well as the richest.

In addition to rent and other income from her lands, Matilda was entitled to claim ‘Queen Gold’, which was one-tenth of every fine paid to the crown.

There were numerous other financial privileges associated with her new position. For example, the city of Warwick was obliged to provide her with 100 shillings for the use of her property, while the City of London paid her tolls on all goods landed at the port of Queenhithe, as well as providing oil for her lamps and wood for her hearth.

Image: Robert Duke of Normandy after unknown artist, c.1677. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Robert’s rebellion

As the 1070s progressed, Matilda, who was at last free from the unrelenting cycle of childbirth, gave full vent to her ambitions. These centred on her first-born (and favourite) child, Robert.

Even though William commanded a huge realm that spanned both sides of the Channel, he refused to cede any power to his eldest son and heir, whom he viewed as feckless and arrogant. By 1077, Robert had grown so frustrated by his lack of power that he decided to wrest it from his father by force.

Matilda entirely supported her son over her husband and secretly funded his rebellion. This almost ended in William’s death when his forces clashed with Robert’s at Gerberoy, northern France, in early 1079. Father and son fought each other in the battle.

Robert gained the upper hand but flinched from delivering the killer blow either through an attack of conscience or, as some chroniclers have it, because he only recognised his father at the eleventh hour. In the aftermath, Robert fled to exile and never again challenged his father’s rule.

When Matilda’s part in the rebellion was discovered, William upbraided his consort in front of the entire court: ‘The wife of my bosom, whom I love as my own soul, whom I have set over my whole kingdom and entrusted with all authority and riches, this wife, I say, supports the enemies who plot against my life, enriches them with my money, zealously arms and succours and strengthens them to my grave peril.’

In response, Matilda sank to her knees and delivered an impassioned speech – the only surviving record of her spoken word.

O my lord, do not wonder that I love my first-born child with tender affection. By the power of the Most High, if my son Robert were dead and buried seven feet deep in the earth, hid from the eyes of the living, and I could bring him back to life with my own blood, I would shed my life-blood for him and suffer more anguish for his sake than, weak woman that I am, I dare to promise.

Matilda of Flanders’ recorded speech on being found to have taken part in her son Robert’s rebellion against her husband

It was a masterly performance. Matilda had betrayed William 'the Conqueror', one of the most feared leaders in Western Europe, a man notorious for his ruthlessness and brutality. He could well have sent her into exile – or worse. But in pleading the strength of her maternal feelings – something that was both expected and admired in a royal spouse – she helped justify her treacherous actions.

Matilda’s speech probably saved her life and secured William’s public forgiveness. But he deprived her of all power from that day forward.

A family torn apart

Matilda’s support for her eldest son’s rebellion made one of the most powerful dynasties in the world look fragile and vulnerable. William could now no longer rely upon either his wife or his eldest son to take care of his dominions during his frequent absences.

Matilda spent the rest of her life trying to reconcile her husband and her eldest son, to little avail. The stress caused by the rift in her family took its toll on her health; this formerly energetic and robust woman was recorded as seeking a cure for lethargy.

In July 1083, Matilda was present at a brief meeting between William and Robert at Caen, but the two men became estranged again shortly afterwards.

The death of Matilda of Flanders

With her family relationships deteriorating, so did the Queen’s health. Matilda of Flanders died in the early hours of 2 November 1083, aged about 52.

Growing apprehensive because her illness persisted, she confessed her sins with bitter tears and, after fully accomplishing all that Christian custom requires and being fortified by the saving sacrament, she died.

Orderic Vitalis

Image: Eglise de la Sainte Trinite, Abbaye-aux-Dames, Caen, Basse-Normandie, France. Matilda and William commissioned this abbey as a mark of their gratitude. © Panther Media GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Matilda was buried in La Trinité, the abbey she had founded in Caen and where her daughter Cecilia had been enrolled as a novice 17 years earlier.

An epigram by the contemporary poet Fulcoius, Archdeacon of Beauvais reads:

'If she could be brought back from death through tears,

Money, fair or foul means, then rest assured

There would be an abundance of these things...

Let this be the inscription [on her tomb]:

“Matilda, queen of the English

Known for her twofold honour, ruled over the Normans

But here rests entombed in good state... A source of glory and grace.'

William was consumed with grief at the death of the woman whom he confessed to love ‘as my own soul’, and was said to have wept profusely for many days afterwards. He never remarried and according to one contemporary, ‘from that time forward, he abandoned pleasure of every kind’.

After the death of his illustrious queen… King William, who survived her for almost four years, was continually forced to struggle against the storms of troubles that rose up against him.

Orderic Vitalis

Image: Matilda's son, William II, depicted at his coronation. Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Matilda of Flanders’ legacy

Matilda’s death certainly caused a profound shift in William I’s behaviour. While she had promoted peace and conciliation, ‘after her death, he [William] became a thorough tyrant’, according to another contemporary chronicler.

It was suddenly obvious just how great a restraining influence Matilda had exercised over her husband, whose increasing brutality threatened to destroy the fragile integration of Normans and Saxons in England that she had fostered.

Despite its often turbulent nature, William and Matilda’s marriage had been one of the most successful partnerships in medieval Europe. She was his mainstay for more than 30 years, and had been one of his most valued advisers. She had also proved a wise and capable ruler during his long absences on campaign.

As expected of a medieval queen, she had borne him many children to secure his dynasty. It had been her bloodline that had enabled him to pursue so vigorous a claim to the English throne.

Matilda’s achievements as Duchess of Normandy and Queen of England had been considerable. She had carved out a position of power and influence in the male-dominated political arena of both countries, and in so doing had confounded the conventional stereotypes of women.

Image: Matilda of Flanders by H.B, 19th century. No contemporary portraits of Matilda survive. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Far from being a meek and submissive wife and consort, subject entirely to her husband’s will, Matilda had wielded authority in her own right for more than three decades.

She paved the way for successors such as Eleanor of Aquitaine and Isabella the ‘She-Wolf of France’, both of whom supported their sons in rebellion against their husbands.

Matilda was the mother of two kings but her influence over the English monarchy would far outlive her youngest son, Henry I, who died in 1135. Her bloodline would continue for more than a thousand years. All sovereigns of England and the United Kingdom are directly descended from this remarkable woman, including King Charles III.

Listen to the podcast

Matilda of Flanders

Matilda of Flanders is the formidable consort of William the Conqueror, yet she is relatively unknown in the story of the 1066 conquest of England.

In this episode of the Historic Royal Palaces Podcast, Chief Historian Tracy Borman makes her pitch for the pivotal role Matilda played as a champion for female sovereignty, and for her contribution to arguably the most successful dynasty in medieval Europe, the Normans.

More episodesPodcast Transcript

Author:

Tracy BormanBrowse more history and stories

William the Conqueror

England's first Norman King

Jewish Medieval History at the Tower of London

The Tower of London holds a principal place in the complex story of England's Medieval Jewish community.

Eleanor of Provence

A powerful and political Queen

Explore what's on

- Things to see

Medieval Palace

Newly refurbished in May 2025, discover the colour, splendour, and people of the medieval Tower of London.

-

Open

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

White Tower

Marvel at the imposing White Tower, a magnificent example of Norman architecture at the heart of the Tower of London.

-

Open

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

St John's Chapel

An architectural gem in the White Tower.

- Open daily

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

Shop online

Shop Medieval

Step back in time with our medieval inspiration collection, full of fascinating ornaments and homewares for your collection.

From £3.50

Shop Kings & Queens of England

Discover our informative and best selling range, inspired by the incredible history of the Kings and Queens of England.

From £4.99

Tower of London Navy Raven Sweatshirt

Inspired by the infamous ravens of the Tower of London, this sweatshirt will keep you warm on those chilly days.

£38.00