Henry III's wife and close collaborator

Eleanor of Provence was Queen of England, wife to Henry III, and one of the most influential consorts in English medieval history.

Intelligent, political and courageous, Eleanor joined the long tradition of medieval queens taking an active role in politics. She was a key mediator, intercessor, and adviser to her husband. She fiercely defended her family but was often blamed for the King’s unpopular policies.

As co-regent when Henry went overseas in 1253, Eleanor represented the King’s interests in parliament. In 1263, during the Second Barons’ War, rebels besieged the Tower of London – Eleanor defiantly left by boat whilst her husband negotiated. She later coordinated a rescue attempt for her captured son Edward (the future Edward I).

Header image: Henry III and Eleanor of Provence returning by sea from Gascony. Courtesy British Library (Royal 14 C. VII)

Did you know?

‘Queen consort’ is a term for the king’s wife, but we use ‘queen’ for short. Eleanor was Queen of England through her marriage to Henry III.

Eleanor’s early life

Eleanor of Provence was probably born in 1223 in Aix-en-Provence, in present-day southern France. She was the second daughter of Count Raymond Berengar V of Provence and Countess Beatrice of Savoy. Unfortunately, details about her early life and education remain scarce, as is often the case for medieval royal and noble women.

All three of Eleanor’s sisters ruled as queens consort alongside their husbands. Her eldest sister, Marguerite, married King Louis IX of France in 1234. In 1243, Sanchia married Richard of Cornwall, Henry III’s brother, who was elected King of the Romans (or King of Germany) in 1257. And her youngest sister, Beatrice, married Charles of Anjou in 1246, who became King of Sicily through conquest in 1266.

Eleanor and her sisters, particularly Marguerite, maintained close ties throughout their lives and frequently exchanged letters.

Image: Drawing of the marriage of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence from Matthew Paris' 'Chronica Maiora'. Courtesy British Library (Royal 14 C. VII)

Queen Eleanor: marriage to Henry III

Eleanor of Provence was married to the 28-year-old Henry III when she was just 12 years old. Their wedding took place in Canterbury Cathedral on 14 January 1236, and she was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 20 January 1236.

Through this union, Eleanor acquired the titles of Queen of England, Lady of Ireland, Duchess of Normandy and Aquitaine, and Countess of Anjou (the latter two lost in 1259 after the Treaty of Paris).

What made a good medieval queen?

Medieval queens had a vital role at court. While they were expected to give birth to at least one male heir (ideally several) to continue the dynasty, they also had several political and diplomatic roles.

Like Matilda of Flanders and other queens before her, Eleanor of Provence was required to use her influence in moderating the king’s behaviour.

Often chosen from other countries, medieval queens were not supposed to allow foreign influence to upset the reputation of the king. In reality, the rulers and nobles of medieval Europe were closely associated and often blood relatives. Many English nobles held lands overseas and frequently travelled to conduct business and diplomacy. Queens were often vital in maintaining cordial relations.

Closer to home, religion was central to medieval royal life, and therefore Eleanor understood her duty to support the Church and demonstrate personal piety. Queens used their patronage wisely and supported the nobility without undue favour on any one body. They supported the ambitions of their children – the future heirs to the throne – although not to the detriment of the king.

Like all medieval queens, Eleanor of Provence was a complex individual with her own ambitions and priorities. But did she conform or resist these expectations of a medieval queen?

An harmonious marriage

The details that emerge from the English chancery records suggest that Henry III held his wife in high regard. He and Eleanor seem to have enjoyed a mostly harmonious and affectionate relationship.

Henry’s desire to please Eleanor and make her feel comfortable upon her arrival in England is particularly evident in the decoration and construction of her apartments in the royal palaces. Henry ordered the creation of several gardens for the Queen, who had a special love for them.

Throughout their marriage, especially during their early years together, Henry chose the motifs depicted in Eleanor’s rooms. In 1238, he ordered her chamber at the Tower of London to be ‘painted with points and to cause flowers to be painted below the points’. A few years later, he commanded her chamber to be whitewashed and ‘painted with roses’.

However, Eleanor and Henry’s marriage was not without its challenges. In 1252, the royal couple quarrelled, resulting in Eleanor’s temporary banishment from court. The trial of Simon de Montfort over his harsh lieutenancy of Gascony, the vacancy of the church of Flamstead, and the escalating conflict at court between the couple’s respective kin (the Savoyards and the Lusignans) all caused tension.

In response, the King took over Eleanor’s lands, almost certainly suspended her control over the queen’s gold, and sent her away from court.

Eleanor was back by the King’s side in Clarendon a fortnight later, and by 27 November she had regained control over her lands and resources. Once reconciled in 1253, Henry III turned to the Queen with renewed trust. She held an influential role in the kingdom’s politics during the following years of his reign.

Image: The Lanthorn Tower at the Tower of London, which was probably part of Eleanor of Provence’s apartments in the medieval period. © Historic Royal Palaces

Eleanor of Provence at the Tower of London

The Medieval Palace at the Tower of London was built in the 1200s for Eleanor’s husband Henry III, and her son Edward I. Kings and queens – including Eleanor – ate, entertained, worked, worshipped, and slept here. The palace was expensively furnished and richly decorated with colourful wall paintings, textiles, and tiles.

The Lanthorn Tower, built in 1220-38, was probably part of Queen Eleanor’s apartments. Today, it is part of the Medieval Palace, which you can explore on your visit.

Eleanor of Provence: powerful Queen Consort

In 1253-54, Eleanor was appointed as Henry’s co-regent alongside his brother Richard of Cornwall during the King’s absence on a military campaign in Gascony.

During this time, Eleanor managed financial affairs, summoned a parliament, and maintained frequent communication with the King, keeping him informed of news and matters in England. She did all of this while being pregnant and giving birth to her fifth child.

The Queen also promoted and advanced her own Savoyard relatives and associates to positions of wealth and power. Thanks to her influence, her uncles (Peter, Boniface, William, and Thomas of Savoy) secured multiple titles and advantageous positions.

The Savoyards emerged as one of the two main factions at court, actively rivalling the Lusignans, the King’s half-siblings. Eleanor’s influence in this area of court life brought with it strong criticism from the English nobility; the Savoyards were viewed as ‘aliens’ and foreigners benefiting excessively from the English King’s generosity and wealth.

Eleanor as a mother

Even with all of her power and influence, what was really expected of Eleanor – and any medieval queen consort – was children (specifically, sons) to continue the dynasty. During the medieval period, successfully bearing the King’s sons could strengthen a royal bride’s influence alongside her husband.

The birth of Prince Edward (the future Edward I) in 1239 solidified Eleanor’s position at court. Eleanor and Henry’s subsequent children included:

- Margaret (born 1240), who became Queen of Scots through her marriage to Alexander III of Scotland;

- Beatrice (born 1242), who married John, the eldest son of John I Duke of Brittany;

- Edmund (born 1245), later Earl of Lancaster.

- Katherine (born 1253), who died in 1257 aged just five.

Eleanor was a caring mother and mourned Katherine’s death deeply; the King and Queen were profoundly affected by her loss.

Royal children lived away from their parents in their own households but, even before Katherine’s death, Eleanor regularly kept her children near her. She was particularly moved to stay close to them when they fell ill. She chose to stay with Edward at Beaulieu Abbey in 1246 when he suddenly became very ill and was not fit to travel. Likewise, when Edmund fell ill in 1252-1253, he was attended by three of the Queen’s doctors, presumably under her direction.

She was also an involved grandmother who strongly opposed the marriage of her 13-year-old granddaughter Eleanor, recalling, perhaps, her own experience as a young bride.

Eleanor’s household and court

Throughout her 36 years as Queen Consort, Eleanor developed a complex network of connections that linked her to the kingdom, with her household at its centre.

The queen’s household in the 13th century was not merely a domestic arena but an administrative entity that travelled throughout the kingdom with the queen, comprising more than a hundred people in her service at any one time. Within her household, she had an independent financial and administrative office, known as the wardrobe, responsible for collecting and managing the queen’s revenue.

While Henry selected Eleanor’s personnel during the early years of their marriage, by the 1250s she had full control over these appointments. She became responsible for the day-to-day management of her court and household, a significant duty considering that she and Henry usually lived apart.

Eleanor was a skilled financial administrator, although towards the end of Henry’s life she went into debt thanks to her support of his position during civil war and instability in England.

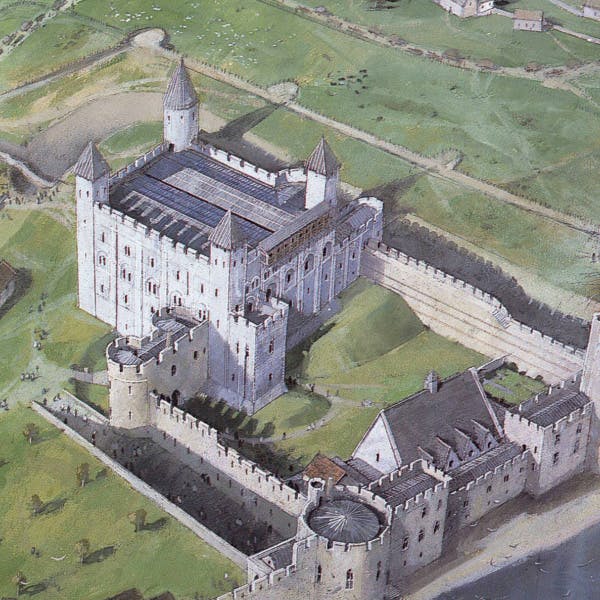

Image: The Tower of London from the south west in about 1240, showing Henry III's enlargement of the castle and the digging of the new moat in progress. © Historic Royal Palaces

The Second Barons' War

Henry III’s reign, and by extension Eleanor’s time as Queen Consort, was marked by baronial reform and the Second Barons’ War (1264-1267). The barons, led by Simon de Montfort, opposed Henry III and the royalist forces.

Although her influence as a key advisor to her husband may be praised today, the contemporary Melrose chronicler described Eleanor as the ‘sower of all discord’ between the King and his barons. It was, however, common to blame queens for their husbands' failures because outwardly criticising kings was frowned upon.

This was not the first time that English barons had opposed royal control. Henry’s father, King John had also clashed with his barons, which led to the charter later known as Magna Carta in 1215. King John’s refusal to abide by these concessions triggered the First Barons’ War (1215-1217).

In April 1258, seven magnates allied and demanded that Henry III agree to reform the realm (‘the Baronial reform movement’). This led to the Provisions of Oxford in 1258 and the Provisions of Westminster in 1259. These measures aimed, among other things, to control and restrict the king’s power and limit the queen’s financial resources.

The years that followed were marked by unrest and tension within the realm, as well as increasing opposition from baronial rebels led by Eleanor’s brother-in-law, Simon de Montfort.

Eleanor is attacked at the Tower of London

In July 1263, Eleanor was attacked by a mob while travelling along the Thames from the Tower of London, on her way to reach her son Edward at Windsor.

This dramatic event left a lasting mark on the Queen, who was more resolved than ever to strengthen the support for her husband.

Eleanor travelled to France that same year, where she sought the alliance of King Louis IX and her sister Marguerite.

The King is captured

Henry’s defeat and capture at the Battle of Lewes in 1264 prompted the Queen to rally support from allies such as the Papacy and the French court.

Although her plan for an invasion of England did not take place, Eleanor did coordinate a rescue attempt for her captured son Edward.

Royal control is restored

Henry III was finally released from custody after the royalist victory at the Battle of Evesham on 4 August 1264. Eleanor returned to England in late October 1265, reuniting with the King at last.

Eleanor continued to support her husband in restoring royal control over the realm. Always financially savvy, she persuaded the Pope to give her more money and settled some of her debts from her time in France.

Religious patronage

As part of their role as consorts, medieval queens were expected to perform acts of religious piety and patronage. Eleanor, married to one of the most pious kings of Western Christendom, was no exception.

Henry III went to chapel every day, visited churches and shrines wherever he went, had large collections of relics, and fed hundreds of poor people each day. Eleanor followed a similar religious routine to her husband. She provided daily food alms to poor people and friars through her household, and made regular payments for alms (charity) and oblations (offerings).

She actively participated in her husband’s devotion to Edward the Confessor and was particularly devoted to the festivities associated with the Virgin Mary.

Eleanor also offered patronage to religious buildings, including the hospital of St Katherine by the Tower of London, refounded in 1273 to commemorate Henry III’s death. She was also patron of the Dominican priory at Guildford, established in 1275 after the death of her grandson Henry.

Image: Corbel head of a queen, possibly Eleanor of Provence, in the Muniment Room of Westminster Abbey. Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

Queen Dowager, powerful landowner

The death of Henry III

Henry III died on 16 November 1272, aged 65. Eleanor was now Queen Dowager (a term for a King’s widow) and mother to the new King, Edward I.

Eleanor deeply mourned her husband’s death; it is possible that she kept his heart with her, as it only reached the Abbey of Fontevraud in 1292 after her own death. The division of the royal remains into different parts (typically the body, the viscera, and the heart) for burial in separate locations was a common practice among 13th-century English monarchs, and was also observed in other Western kingdoms such as France.

Eleanor as a widow

During the 1270s, Eleanor remained a prominent figure in the realm, maintaining frequent communication with her son Edward I and offering her advice and counsel. She also had wealth alongside this influence; as a widow, she had access to a set of lands known as her dower lands, which established her as one of the wealthiest people in the kingdom.

Like her queenship, Eleanor's widowhood was not without controversy. Eleanor was criticised by her contemporaries for the harsh treatment of tenants on her lands, particularly at the hands of her officials, such as William of Tarrant.

Eleanor of Provence and anti-Jewish prejudice

England became home to a large Jewish community after the Norman Conquest of 1066. Jews were initially protected by English kings but taxed heavily in return. Many Jews and Christians lived peacefully as neighbours, but Jews also experienced prejudice and violence.

Eleanor exhibited anti-Jewish attitudes and in 1275, she expelled the Jews from her dower lands. This marked a significant step toward the expulsion of Jews from England in 1290, which was conducted by her son Edward I. Many Jews were sent into exile from the wharf outside the Tower of London.

Edward built St Thomas’s Tower within the Medieval Palace between 1275-9, in part using taxes from England’s Jewish community.

Eleanor becomes a nun

In the final decade of her life, Eleanor retired to the nunnery of Amesbury Abbey in Wiltshire, where she became a nun in 1286. At her insistence, she was joined in this retirement by her granddaughter Mary, the daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile.

Even after joining Amesbury, Eleanor retained her rights over her lands and continued to engage with secular matters.

Death, burial, and legacy

Eleanor of Provence died at Amesbury on 24 June 1291. Her body was buried in the same priory where she had spent the last years of her life, rather than in Westminster Abbey alongside Henry III. Her heart was buried separately at the Grey Friars in London, a common practice among the English royal family.

What type of queen was Eleanor of Provence?

Throughout her life, Eleanor was a loving mother and involved sister, as well as a pious Queen. A skilled household administrator, she secured considerable wealth for herself.

As a key advisor to her husband, Eleanor was able to advance the position of her own relatives at court, which also led to animosity from many contemporaries who perceived her as a threat. Above all, Eleanor was a powerful consort and an intelligent woman, whose influence was profoundly felt during her time.

Watch: Getting dressed as a medieval queen

Medieval stories and fairy-tales show us long gowns, big sleeves, and tall conical hats for princesses. But how accurate is this? What did medieval women really wear?

In this video, historical interpreters go through all the stages of dressing for medieval women, to create an outfit fit for a queen at the Tower of London.

Watch on YouTubeThis content is hosted on YouTube

This content may be using cookies and other technologies for which we need your consent before loading. To view the content, you need to enable cookies for "Targeting Cookies & Other Technologies".

Manage CookiesVideo transcript

Watch a transcript of this video on YouTube. A link to the transcript can be found in the description.

Browse more history and stories

Jewish Medieval History at the Tower of London

The Tower of London holds a principal place in the complex story of England's Medieval Jewish community.

Coronations Past and Present

An ancient ceremony, largely unchanged for a thousand years

Elizabeth of York

The original Tudor Queen, and wife of Henry VII

Explore what's on

- Things to see

Medieval Palace

Newly refurbished in May 2025, discover the colour, splendour, and people of the medieval Tower of London.

-

Open

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

St John's Chapel

An architectural gem in the White Tower.

- Open daily

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Battlements

Walk the defensive walls and huge towers that have guarded the Tower of London for centuries.

- Open

- Tower of London

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

Shop online

Shop Medieval

Step back in time with our medieval inspiration collection, full of fascinating ornaments and homewares for your collection.

From £3.50

Shop Kings & Queens of England

Discover our informative and best selling range, inspired by the incredible history of the Kings and Queens of England.

From £4.99

Tower of London Navy Raven Sweatshirt

Inspired by the infamous ravens of the Tower of London, this sweatshirt will keep you warm on those chilly days.

£38.00