Highlights

The display of art at Hillsborough Castle in Northern Ireland has been selected to represent both the history and the contemporary use of the house as a royal and government residence. It has been drawn from several sources, including The Royal Collection, The Schorr Collection and collections featuring contemporary Irish artists.

The paintings are displayed to reflect the themes and historical use of the rooms where appropriate, including rule, power, law and justice, and the Downshire family history. There are original works of art hanging alongside later copies, or interesting ‘after’ or ‘school of’ works, inspired by more famous artists.

Here is a more in-depth look at some of the highlights of the current Hillsborough Castle hang and the stories they depict.

Did you know?

Copies of original paintings referred to as ‘studio of’ or ‘school of’ have usually been created by artists in training under a famous painter.

Image: The South Terrace, Hillsborough Castle, © Historic Royal Palaces

The history of art at Hillsborough

Paintings in an Irish ‘Big House’, as these aristocratic private homes were known, were usually created by minor jobbing artists. These painters travelled around the country to paint for wealthy clients.

However, we know Hillsborough originally displayed work by one prominent artist, George Romney (1734-1802). From the house inventories going back as far as 1747, we can see that family portraits hung in the Dining Room, as was traditional.

Satirists were also popular, and these early inventories showed that the family owned many prints by William Hogarth.

State Entrance Hall

This room has always been the entrance to the building, and a space in which to welcome visitors, from Queen Elizabeth II to pop star Gary Barlow.

Image: © Historic Royal Palaces

The hang in the State Entrance Hall shows all the main protagonists involved in the history of the house, including Wills Hill, 1st Marquess of Downshire, painted in 1791 by George Romney.

© Historic Royal Palaces; Accepted in lieu of Inheritance Tax by HM Government in 2023 and allocated to Historic Royal Palaces for Hillsborough Castle. Treatment funded by the Apollo Foundation.

Wills Hill, 1st Earl of Hillsborough (1745)

This portrait of Wills Hill, 1st Earl of Hillsborough, painted by the renowned Scottish artist Allan Ramsay in 1745, captures the Earl at a pivotal point in his career. Wills Hill had begun to shape the development of Hillsborough and influence the politics of Britain and Ireland.

Allan Ramsay (1713–1784), a prominent figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, was deeply influenced by late Italian Baroque and contemporary French art. He would later become the Principal Painter to King George III, solidifying his place in British art history. The portrait is now part of Historic Royal Palaces's collection.

Image: Charles II, after Peter Lely (19th-century copy), Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 407684

Charles II, After Sir Peter Lely

State Entrance Hall

This handsome Stuart was particularly important to the town, and to the Hill family.

During the 1660s Charles II granted Hillsborough borough status.

This gave the family important commercial and legal benefits, including the right to send representatives to parliament.

This copy of the 1672 original painting was commissioned by Queen Victoria in the 19th century.

Although the Queen was a Hanoverian, she took a keen interest in her glamorous Stuart ancestors.

We don’t know exactly when this picture was painted, but it was hanging in St James’s Palace by 1865.

Image: Mary II (1662-94) when Princess by Peter Lely, c1672, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 404918

Mary II when Princess

State Entrance Hall

The Dutch artist Peter Lely depicts the 10-year-old Princess Mary, daughter of James II and sister to the future Queen Anne, as the Roman goddess Diana.

As well as being a huntress, Diana was also the virtuous protector of young women, and perhaps Lely evoked Diana for a reason.

Five years after this was painted, tall, attractive Mary was told she was to be sent away to the Netherlands to marry her cousin, Prince William of Orange, who was at least 10cm shorter than her, and considerably older.

The young Princess ‘wept all day that afternoon and all the following day’.

Despite this unpromising start, the couple grew to love each other. Mary returned to England in 1668 after the ‘Glorious Revolution’ to rule jointly with her husband, William III.

Mary II died of smallpox in 1694 aged only 32, leaving William heartbroken.

Ante Room

The ‘heart of the castle’, providing access to some of the most important rooms of this stately home.

Image: © Historic Royal Palaces

The Ante Room formed part of the original house built in the mid-18th century. It was created from a much smaller hallway in 1936, following a fire in 1934. The room features art depicting members of the Hill family, including the Ombersley miniatures and a bust of Wills Hill, First Marquess of Downshire, who is credited with developing much of the town of Hillsborough.

Image: These miniatures were gifted to Historic Royal Palaces by the trustees of the Sandys Trust (Registered Charity Number 1168357)

Mary Hill, Marchioness of Downshire

These miniatures are named after Ombersley Court, the Sandys family estate, which Mary Hill later inherited. They were kept in the collection of the late 7th Baron Sandys, a descendant of the Hill family who lived at Hillsborough Castle.

Mary was a wealthy heiress who married Arthur Hill in 1786 and the couple had seven children. This miniature was painted around the time of her marriage by Richard Cosway, who also painted her husband. Cosway was one of the most popular miniaturists of his time and went on to paint the Hill family on several occasions.

After her husband’s death, she was responsible for running the Downshire estates until her eldest son came of age. She was an important political figure who was involved in election campaigns in county Down.

A well-known society hostess, Mary was established in many aristocratic circles of Regency London and was a close friend to the Prince Regent (later George IV).

Mary, Marchioness of Downshire: A Life in Miniature

Research and Interpretation Producer Emma Lawthers takes a brief glimpse into the lives of Mary and the Hill family of Hillsborough Castle, as seen through the lens of a unique object.

Image: These miniatures were gifted to Historic Royal Palaces by the trustees of the Sandys Trust (Registered Charity Number 1168357)

Arthur Hill, 2nd Marquess of Downshire

Ante Room

Arthur Hill was the son of Wills Hill, 1st Marquess of Downshire, who built Hillsborough Castle. He opposed the Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland and was consequently punished politically by the government when the Union came into effect in 1801.

His wife Mary felt his ill treatment contributed to his death by suicide on 7 September 1801. Arthur’s miniature was painted at the same time as Mary’s. Both of their miniatures contain neatly plaited locks of hair on the reverse.

Throne Room

This splendid space is the ceremonial heart of the castle, and when it was created in the early 19th century as a Saloon, it was the picture gallery of the house.

Image: © Historic Royal Palaces

Traditionally, here was where the Downshire family, like other aristocrats, would hang their most prized ‘history’ paintings. These featured stories from the Bible, mythology and ancient history, to reflect an aristocratic classical education.

Image: Stag Hunt at Versailles (detail), by Jean Baptiste Martin, c1700, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 406958

Stag Hunt at Versailles

Throne Room

This painting and its pair, Hawking Party at Marly, were bought by art-loving British monarch George IV following the French Revolution. They evoke the lost monarchy of France and feature the Duke and Duchess of Burgundy and their splendid court – something to which the King aspired.

George IV adored anything French – food and furniture as well as art – and he was an extravagant collector. He filled his palaces with collections of European old masters and more contemporary work. Displaying paintings of the lost French monarchy was an attempt to show solidarity with them, post-Revolution, while of course being available more cheaply as the new French government sold them all off. George IV paid only 40 guineas for both paintings from a Parisian dealer!

Image: Hawking Party at Marly (detail), by Jean Baptiste Martin, c1700, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 406957

Hawking Party at Marly

Throne Room

The Duchess of Burgundy, aged around 15 is riding side-saddle on a white horse at the Chateau of Marly, seen in the background.

Her arrival in the French court, aged 12, to marry the Duke was described as ‘a breath of fresh air’ but sadly she died when she was 26 from a measles outbreak that also killed her husband and eldest son.

Image: The Family of Darius before Alexander (above), Studio of Sebastiano Ricci, c1700-30, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 404768

The Family of Darius before Alexander

Throne Room

This is another painting in the Throne Room chosen for its classical subject matter. The scene depicts the story of the captured family of the Persian Emperor Darius III pleading with Alexander the Great for their freedom.

It is a version of an earlier famous painting by Paolo Veronese, painted in 1565-7.

The original first hung in Venice, where it was much copied by aspiring artists on their ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe. This later reduced and simplified version was painted by an apprentice of Sebastiano Ricci, a celebrated Venetian artist of the 1700s, under supervision in his studio.

The story has a happy ending: Darius had fled from the battlefield, allowing his family to be captured by Alexander, who refused to release them despite their desperate pleas. However, Alexander treated them generously and eventually married Darius’ daughter.

Red Room

The paintings in this room appear as a ‘cabinet hang’, typical of the type where many small, highly-decorative paintings are densely displayed.

Image: © Historic Royal Palaces

A cabinet was usually a private room in which intimate discussion took place. The round table was a deliberate choice, allowing equality of seating for all participants.

The cabinet hang was chosen here as it is particularly appropriate for the Red Room. During the 1980s and 1990s, many of the delicate negotiations of the Peace Process were held in here.

It was in the Red Room that Queen Elizabeth II met Irish President Mary McAleese in 2005, for what was described at the time as ‘a historic event’.

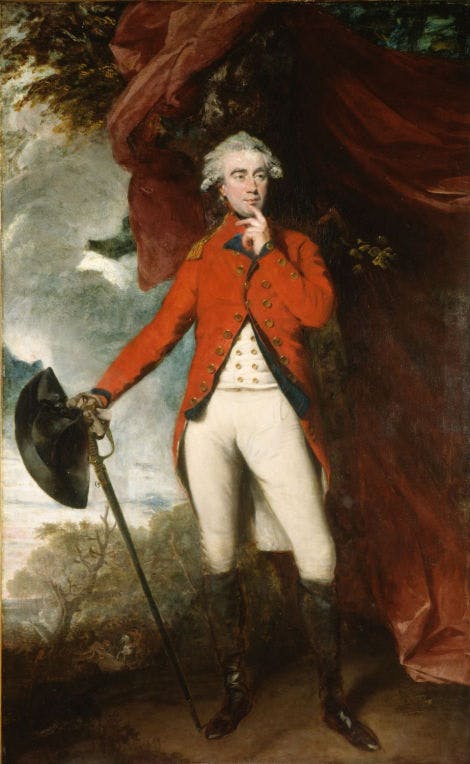

Image: Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 2nd Earl of Moira and 1st Marquess of Hastings, by Sir Joshua Reynolds c1789-90, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 407508

Francis Rawdon-Hastings

Red Room

A full-scale portrait of this kind is not usually found in a ‘cabinet hang’, but it is displayed here as it’s one of Reynold’s finest paintings in an impressive career, and Hastings has links with the area surrounding Hillsborough, as he was the 2nd Earl of Moira, the nearby town.

This portrait was commissioned by Rawdon-Hastings as a gift for the Duke of York. As required by courtly etiquette, the Duke gave Hastings a portrait in return. George IV (who had already also exchanged portraits with Hastings) purchased this painting in 1827.

Doubtless, the art-loving King appreciated the fine quality of Reynolds’ work in capturing the colonel in an intelligent and confident pose, despite the artist reportedly suffering from problems with his vision at the time.

Image: ‘School of Athens’ (detail) by Raphael, copy by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1750, © Schorr Collection

School of Athens by Raphael, copy by Sir Joshua Reynolds

Red Room

This sketch copy of Raphael’s vast, celebrated fresco in the Vatican was created by Reynolds during a trip to Rome in the spring of 1750, where he made several copies of Old Masters. Reynolds encouraged younger artists to study Renaissance works of art. He emphasised the importance of Italian art at the Royal Academy and the merit of copying works in order to refine and develop new skills and techniques.

State Dining Room

This room has been the scene of many grand celebratory meals.

Image: © Historic Royal Palaces

In 1829, Lord Downshire held a candlelit feast to celebrate the Twelfth Night of Christmas, with over 150 guests invited.

The hang in the State Dining Room reflects themes of food, dining and portraits, both royal and of the Downshires.

Image: Dead Hare and Partridges with Instruments of the Chase, Jan Weenix, 1704, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 403375

Dead Hare and Partridges

State Dining Room

Dutch artist Jan Weenix specialised in painting hunting-trophy pictures. A dead hare was one of Weenix’s repeated motifs.

This elaborate scene depicts the equipment associated with hunting, along with the dead game situated in parkland or a garden. This painting was part of a collection of 86 by Dutch and Flemish artists, bought by George IV.

Image: Portraits of Queen Charlotte and George III (detail), attributed to Allan Ramsay, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 402413 and RCIN 402412

Queen Charlotte and King George III

State Dining Room

The artist Sir Allan Ramsay had already painted George III as Prince of Wales in 1758 for John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, George III’s tutor and mentor. The success of that portrait led to Ramsay painting the state portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte in coronation robes seen here.

Paintings of the King and Queen were in high demand from aristocrats like the Downshires, keen to show their allegiance to the monarch. Ramsay’s studio in Soho, London, was described as being ‘crowded with portraits of His Majesty in every stage of their operation’.

There were orders for 150 pairs, and Ramsay was determined to paint each of them himself but eventually employed several assistants including David Martin and Philip Reinagle to help him. They painted these, with Ramsay himself painting the hands and faces.

Image: This portrait was gifted to Historic Royal Palaces by the trustees of the Sandys Trust (Registered Charity Number 1168357)

Lord Marcus Hill

State Dining Room

Marcus Hill was the son of Arthur, 2nd Marquess of Downshire and his wife Mary, née Sandys. This portrait of Marcus was painted around 1816 by Thomas Lawrence, a popular portrait artist who would later paint many famous figures of his era, from Queen Charlotte to the Duke of Wellington.

Here, Marcus is pictured at 18 years old, just before his role as secretary to the British envoy to Spain. He is wearing court uniform, commonly worn for diplomatic service in the early 19th century.

The portrait was commissioned by Marcus’ mother, but Lawrence was not the first artist she had in mind. Marcus’ sisters recorded in their diary that their mother went to George Hayter’s studio but he was unavailable since he was ‘going abroad in a day or two’. They later visited Lawrence’s studio and were impressed by the ‘beautiful and striking likenesses’ in his art. Marcus’s sisters stayed with him while he sat for his painting.

State Drawing Room

This elegant space, with its wonderful view of the gardens, was originally designed as a library, holding many thousands of books, which were sold at auction in 1907. It dates from around 1810 but was rebuilt after a major fire at the castle in 1934.

Image: © Historic Royal Palaces

The hang in the State Drawing Room shows works by famous contemporary Irish artists, some with royal patronage.

Image: On loan from the Crawford Art Gallery, Cork

Off the Donegal Coast

State Drawing Room

This work was painted by renowned artist Jack B. Yeats in 1922, one of the most important artists working in Ireland during the 20th century and the first Irish artist to sell a work for over £1 million.

He was the son of the painter John B. Yeats and brother of poet and playwright William B. Yeats. The artist often depicted Irish life and the people of the West, using these subjects to visit the theme of Irish nationality.

In Off The Donegal Coast, Yeats portrays the West Coast of Ireland, showing sailors in their little currach rocked by waves, with fear visible in their eyes. Yeats’ displays an unusual diagonal composition and places our view on the side or above the rescue ship. With his vigorous painting style, energetic brushstrokes and muted tones, Yeats captures a moment of great tension.

Image: Sir Winston Churchill Painting, by Sir John Lavery, 1915. © Historic Royal Palaces

Sir Winston Churchill Painting

State Drawing Room

The famous British Prime Minister with his easel and paints was captured in 1915 by his friend and art tutor, Sir John Lavery.

Lavery was born in Belfast in 1856 and trained in Glasgow and Paris before moving to London, where he became an established society painter.

Churchill did not begin painting until he was 40 years old and learnt from friends such as Lavery and Lavery’s wife, Hazel.

He is depicted here in the garden of Lady Minnie Paget, who lived near London and was an American society friend and contemporary of Churchill's mother.

Lady Grey's Study

This calm, cosy room was created in 1936, two years after the disastrous fire.

Image: © Historic Royal Palaces

The study is named after Lady Grey of Naunton, Esmé Burcher, wife of the last Governor of Northern Ireland.

Image: © Historic Royal Palaces

Preparing the Peace

Lady Grey's Study

A collection of preparatory sketches displayed in Lady Grey’s Study of official portraits of key figures involved in the Peace Talks at Hillsborough Castle.

A collection of preparatory sketches of official portraits which now hang in institutions all over the world are displayed together in Lady Grey's study.

Browse more history and stories

The story of Hillsborough Castle and Gardens

‘The Grandest House in County Down’

Good Friday Agreement

Hillsborough Castle was the scene for key meetings that led to this historic moment in Northern Ireland’s history

Mo Mowlam

A unique Northern Ireland Secretary and Hillsborough Castle resident

Explore what's on

- Things to see

Ante Room

Discover the heart of the castle, which provides access to some of the most important spaces.

-

Closed until castle reopens on 15 March 2026.

- Hillsborough Castle

- Included in combined castle tour and gardens tickets (Members go free)

- Things to see

Red Room

Political history meets royal life and a spectacular collection of art, deep in the heart of Hillsborough Castle.

-

Closed until castle reopens on 15 March 2026.

- Hillsborough Castle

- Included in combined castle tour and gardens tickets (Members go free)

- Things to see

State Drawing Room

Discover contemporary Irish art from the collection of His Majesty The King in this elegant family space.

-

Closed until castle reopens on 15 March 2026.

- Hillsborough Castle

- Included in combined castle tour and gardens tickets (Members go free)

Shop online

Official Hillsborough Castle & Gardens Guidebook

Descriptive, informative, authoritative - this superb guidebook is the best way to learn all there is about Hillsborough Castle and Gardens.

£4.99