Walter Hungerford and the Buggery Act: LGBTQ+ History and Punishment at the Tower of London

Date: 19 February 2021

Author:

Olivia Martin

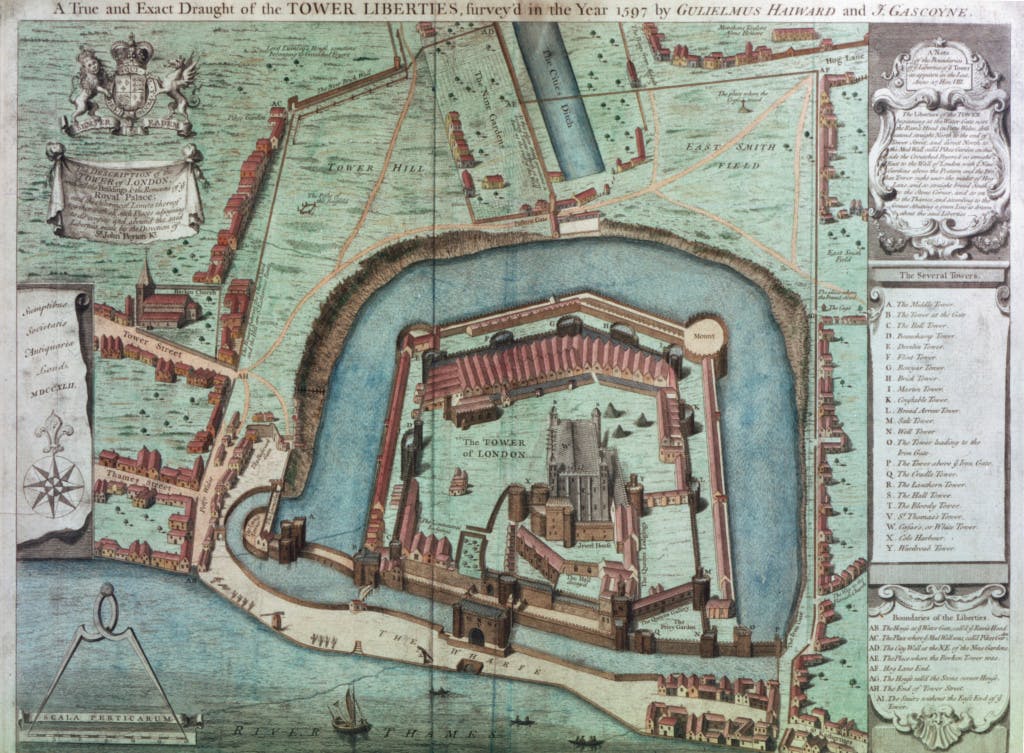

If you visit the Tower of London, you can walk where some of the most significant events in British history happened. Today, as part of LGBT History Month, we examine a darker side of the Tower's history. On 28 July 1540, the first execution under the Buggery Act, the first civil law to criminalise homosexual behaviour, happened on Tower Hill. I would like to take you back into its past to look at this historic event.

I'm Olivia, an MA student currently on placement with the Curators team at Historic Royal Palaces. Despite a lifelong love of history, including a degree in it, I have never been taught much about LGBTQ+ history due to its absence from school and university curriculums. Writing this blog post is making a very small start on redressing a huge imbalance, shedding new light on elements of the Tower's story previously unseen.

Image: Henry VIII, from the stained glass window at Hampton Court Palace, installed in 1845. The legacy of Henry VIII's Buggery Act of 1533 lasted for centuries after his reign. © Historic Royal Palaces

Henry VIII was the first to criminalise homosexual activity in civil law in the form of the Buggery Act of 1533. Such behaviour had previously been regulated by ecclesiastical, or Christian, courts. The Act defined same-sex sex as 'the detestable and abominable vice of buggery', stating those found guilty should be sentenced to death. Members of the clergy, such as priests and monks, could also be executed under the Act, despite their immunity from being executed for murder. This implies that murder was seen as a lesser crime than buggery, but could also suggest that Henry VIII was using civil law to limit the powers of the Catholic Church - the Act of Supremacy that declared him Supreme Head of the Church of England was passed only one year later. Whatever Henry VIII's motives, the Buggery Act was to remain in law in some form in England and Wales until 1967, indicating the long-lasting impact of his reign on the modern world.

The first man to ever be executed under the Buggery Act was executed on Tower Hill, and so this week we turn to the LGBTQ+ stories at the Tower of London, from the landed gentry to the anonymous linen draper's apprentice. Historic LGBTQ+ stories are often related to crime, as reports of their arrest or criminal trial are preserved in a way that diaries, if they were kept, rarely survive.

To learn what the impact of the Buggery Act was for Henry VIII's fellow Tudors, let me introduce you to Walter Hungerford (1503-40), eventually Lord Hungerford of Heytesbury. He was born an only child to Sir Edward Hungerford and Jane Zouche, inheriting his father's estate at the age of nineteen in 1522. After spending several years as an Esquire of the Body, or personal attendant, to Henry VIII, Hungerford rose to prominence after his marriage to his third wife, Elizabeth Hussey. In 1532, Hussey's father, John Hussey, 1st Baron Hussey of Sleaford, introduced Hungerford to Thomas Cromwell, who was at that point a favoured member of the Privy Council.

Hungerford found favour with Cromwell in this period, being rewarded for his service in June 1536 by being called to Parliament as Lord Hungerford of Heytesbury. Although his career was accelerating, his personal life was much less rosy. His wife Elizabeth wrote to Cromwell in 1536 to inform him of Hungerford's treatment of her, which included having been locked in a tower at Farleigh Hungerford Castle for three or four years. She claimed Hungerford had 'once or twice heretofore poisoned me', as well as continually starving her. Elizabeth even asked for Cromwell to help her get a divorce, and it is here that we get the first implication of Hungerford as a potentially queer individual. She claims that if Cromwell would not help her, she 'may sooner object such matters against him [Hungerford] with many other detestable and urgent causes than he can against me, as he well knows'. This could imply homosexual behaviour, or buggery, on Hungerford's part. However, Cromwell appears to have ignored the letter, as Hungerford continued to attend important events.

In 1540, however, both Cromwell's and Hungerford's fortunes changed. Hungerford had employed a man named William Bird as his chaplain, who was suspected of involvement with the 1536 Pilgrimage of Grace, which had campaigned against Henry VIII leaving the Catholic Church. Hungerford was accused of employing Bird while knowing that he was against the King. On top of this, Hungerford was also charged with employing men to do witchcraft to determine how long Henry VIII would live. The final charge was the 'detestable vice and sin of buggery', or same-sex sex, with his servants. This final charge was likely added onto Hungerford's case to embarrass him. The fact that Elizabeth's letter, Hungerford's court records and the Buggery Act itself all use the word 'detestable' supports the argument that Elizabeth was referring to buggery when she said it, and thus it was not a complete secret in Hungerford's life and that at least a few people were aware of it.

Image: Thomas Cromwell, after Hans Holbein the Younger oil on panel, early 17th century, based on a work of 1532-1533. Cromwell was responsible for passing the Buggery Act legislation through Parliament. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Treason, witchcraft and buggery proved to be a fatal combination, and Walter Hungerford was executed at Tower Hill on 28 July 1540, the first person to be executed under the Buggery Act. He was executed on the same day as Thomas Cromwell.

Hungerford's trial and execution marked the beginning of centuries of prosecutions under the Buggery Act. Although members of elite society are often better documented, we do find evidence of LGBTQ+ lives in other parts of society. For example, we know about a punishment on Tower Hill in January 1725 that was reported in local papers. The incident involved two men being arrested for an 'attempt to commit sodomy' with a third, younger man. They were sentenced to stand in the pillory on Tower Hill, as well as serve six months in prison. The men are nameless, completely unidentifiable other than that one of them was an apprentice to a linen draper. We will never have the same detailed look into their lives as we do with Walter Hungerford, this single newspaper article describing their trial giving us the most fleeting glance into their world. Despite this, the existence of this article proves to us that they were there, and implies the existence of others that never made it into the papers.

The crime of buggery was reduced from a capital offence to a sentencing of penal labour in 1861, and the Buggery Act, in its modern form, was finally repealed in England and Wales in 1967.

In 2020, queer lives at the Tower became 'Queer Lives At The Tower', a series of tours around the site led by a drag artist, actors and the warding team, bringing the Tower’s LGBTQ+ history to life. From the Buggery Act of 1533 and Walter Hungerford’s execution to the tours of 2020, LGBTQ+ lives have been lived in and around the Tower for centuries, often by individuals whose names have been lost to time, or only briefly appearing in records to let us know they were there. Their presence reminds us that LGBTQ+ people have always been here, but that it is only recently that we have been able to tell their stories.

Olivia Martin

MA Heritage Management Student

Historic Royal Palaces and Queen Mary University of London

Image: In 2020’s 'Queer Lives At The Tower', drag artist Mahatma Khandi took the role of a raven, guiding visitors through The Tower of London’s LGBTQ+ history. © Historic Royal Palaces

More from our blog

Frederick Wright Or Kathleen Woodhouse: A First World War Soldier Who Wished To Live As A Woman

15 February 2022

February is LGBT+ History Month in the UK, which aims to increase the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT+) people through the exploration of their history and stories. Collections Curator Matthew Story explores one such story.

The Real Norman Hartnell: Beyond 'Silver and Gold'

25 February 2022

February is LGBT+ History Month in the UK, which aims to increase the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT+) people through the exploration of their history and stories. Collections Curator Matthew Storey looks at one such story.

Frances Stuart and Barbara Villiers

10 February 2023

Learn about the relationship between Frances Stuart and Barbara Villiers, two of the most influential women at the court of King Charles II.