The Real Norman Hartnell: Beyond 'Silver and Gold'

Date: 25 February 2022

February is LGBT+ History Month in the UK, which aims to increase the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT+) people through the exploration of their history and stories. Collections Curator Matthew Storey looks at one such story.

I think of the long road behind me, leading up to this honour and bringing me to Westminster Abbey. What I suffered, learned and enjoyed on the way, is the story I presently tell.

Prologue, Silver and Gold

Norman Hartnell begins his autobiography at the zenith of his career, sitting in the Queen's Box at Westminster Abbey, about to see the new Queen Elizabeth II crowned in the magnificent coronation dress he had designed. The book, Silver and Gold, published in 1956 is witty, engaging and fabulously quotable, but it is only a partial truth, the face Hartnell wished to show to the world. The real man was more fascinating, and his achievement more remarkable, than even he would acknowledge.

The Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection, cared for by Historic Royal Palaces, has beautiful examples of Hartnell's clothes, designs and archives. Understanding his story is important for us to tell the history of royal fashion.

Image: Norman Hartnell, when he was young, and throughout his life, the great designer presented a carefully crafted appearance to the world. A vintage photograph in the Historic Royal Palaces collection. Photographer unknown © Historic Royal Palaces

Humble Origins

In Chapter One of Silver and Gold, Hartnell takes us back to his childhood, telling us that 'my interest in Fashion began with a box of crayons'. He introduces us to the sickly child sitting in bed given crayons and watercolour paints to distract him, filling his school books with doodles of dress designs. In the first few pages Hartnell introduces us to his cousin, friends and even his headmaster, but nothing about his parents, or even where he was born.

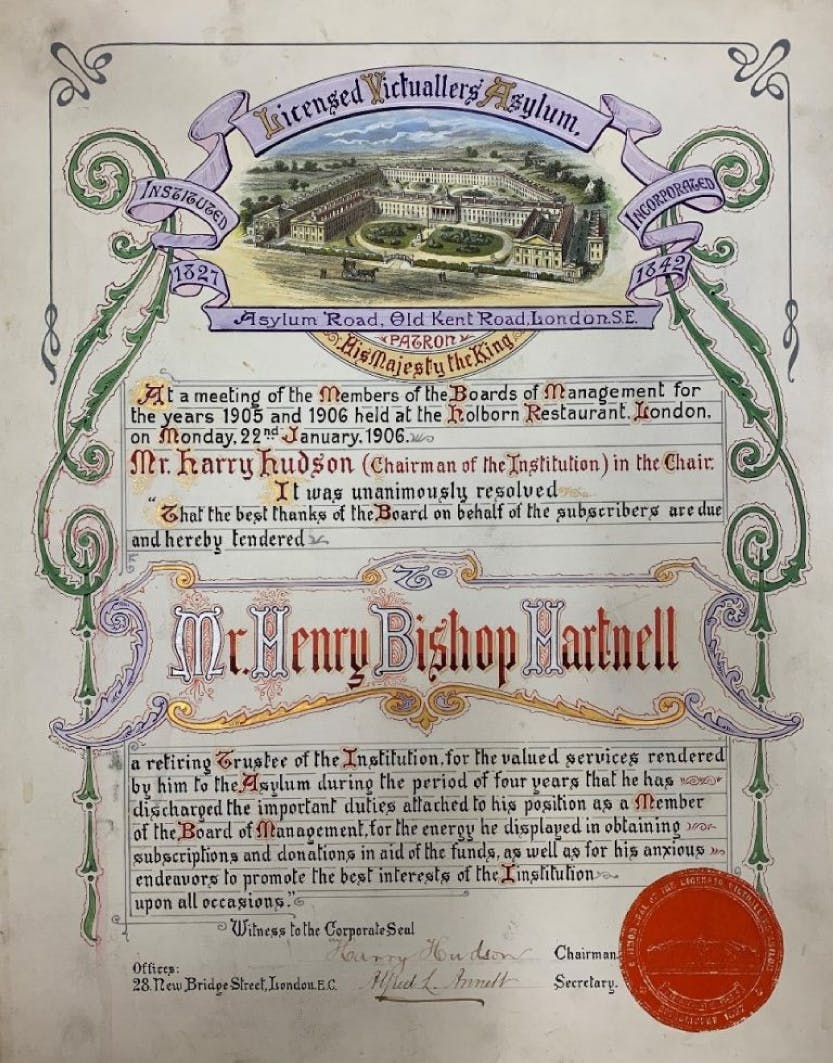

The Historic Royal Palaces collection contains a clue to this obscured past, a certificate issued to his father, Henry Bishop Hartnell, known as 'Bish'. It celebrates his achievements as a trustee of the Licensed Victuallers Asylum, an almshouse for former pub owners who needed housing and support. It shows the high standing Hartnell's father had in his profession as a pub owner and later alcohol wholesaler.

If Hartnell had been a little more honest he might have mentioned his birthplace. The future royal couturier was born above his father's pub, appropriately called The Crown and Sceptre. It still stands on the crossroads of Streatham Hill. Whenever I pass by the pub, I find myself wondering why Hartnell chose to obscure this aspect of his past. I was born only a few miles away myself, so I like to claim Hartnell as a fellow South Londoner. But Hartnell was so determined to control his own narrative that he prevented an episode of This Is Your Life about him being shown in 1960.

While plenty of people who had grown up with Hartnell and who knew his family would have been well aware of his relatively humble origins, he preferred to focus on his later professional achievements and royal, noble and celebrity client list.

The Necessity of Secrecy

Perhaps Hartnell's desire for secrecy came not only from the snobbery of his time, and the need to cultivate a sophisticated image, but a necessity to keep his personal life private. Hartnell was a gay man when sex between men was illegal, and a scandal could have destroyed his professional and social standing. Like many gay men at this time, Hartnell's sexuality was not a secret from everybody, and although a select group of people did know about it, or might have guessed, many people did not. Newspaper gossip columnists even speculated on why Hartnell 'couldn't find the right girl'.

The most significant expression of Hartnell's sexuality that relates to his work, was his crossdressing. This was first very publicly displayed when he was at Cambridge, and part of the Footlights drama club. There, as was very common, Hartnell played female roles in all male productions. He also designed the costumes to wear for these roles, which were made up for him by the court dressmaker Myra Salter, based in London. This gave him his first major insight into the designing and making of fashionable women's clothes. Photos of Hartnell in these elegant dresses show how his early design achievements, and crossdressing, were showcased in front of an audience.

Later in his life, Hartnell continued to design feminine clothing to wear himself, which he had his seamstresses make in his own workshops. The orders for these clothes were recorded under the false name, 'Mrs Freeman', to deflect suspicion. This name is perhaps also a touching insight into how wearing these clothes might have made Hartnell feel. Did he feel more free, more authentically himself, in them? Some of the clothing appears to have survived, and it is every bit as beautiful and embellished as you would expect from a Norman Hartnell creation.

We do know that one of Hartnell's staff was aware that these beautiful clothes were intended for her boss. A recent biography of Hartnell opens with an account from 1948 of his bookkeeper, Mrs Godley, returning to the Hartnell offices at 26 Bruton Street in Mayfair, when everyone else had left. There she discovered Hartnell in a full evening dress, evidently waiting for a visitor. Mrs Godley interpreted his choice of clothes as fancy dress, while also finally worked out the true identity of the mysterious Mrs Freeman. Yet she still felt that she shouldn't mention this event to anyone, and didn't for many years. It is likely that Hartnell was waiting for a male visitor, and there is evidence that there was an erotic aspect to his crossdressing. This again suggests that Hartnell was happy to reveal this aspect of his life to a select group of people.

The Culture of the Time

Hartnell's preference for feminine clothing as an expression of his sexuality was a common feature of gay male subcultures in the early twentieth century. In Soho and the west end gay men formed subcultures based around effeminate clothing and behaviour, as a form of self-expression and to affirm a shared sense of identity. This effeminate styling to express homosexuality was formed in opposition to the masculine styling expected of heterosexual men. Quentin Crisp, the later self-proclaimed 'Stately Homo of England' describes this scene when he first discovered it in the 1920s in his memoir The Naked Civil Servant, an altogether different book to Hartnell's Silver and Gold:

The whole set of stylizations that are known as 'camp' was, in 1926, self-explanatory. Women moved and gesticulated in this way. Homosexuals for obvious reasons wished to copy them.

While he notes that: The men of the 'twenties searched themselves for vestiges of effeminacy as though for lice.

Is it any wonder, coming of age in the 1920s, that Hartnell expressed his sexuality in this way, while realising that if it was revealed he would be shamed or even prosecuted? Instead, while his day-to-day clothing was certainly refined and dandified, he chose to be careful who he showed his private clothing choices to. Hartnell was 66 when the 1967 Sexual Offences Act partially decriminalised sex between men in England and Wales and, even after it, homosexuality still carried huge social stigma.

A New Appreciation

So where does this leave us in an appreciation of Hartnell's life and talents? His achievements were extraordinary. He redefined fashion in the 1930s in his designs for crinoline dresses for The Queen Mother. He designed HM The Queen's wedding dress and coronation dress. He dressed celebrities and aristocrats. He grew his business to include diffusion lines and cosmetics, so that everyone could afford a piece of the Hartnell magic. In 1977 he was the first person ever to be knighted for services to fashion.

Perhaps one reason he designed clothing for women so well was because his first experience of designing feminine clothing was for clothes he wore himself in those plays in Cambridge. The sense of joy, fun, glamour, and femininity that define Hartnell's style could be a result of his own sense of freedom when wearing those clothes.

In 2022, we can look back on Hartnell's life and career from the standpoint of a society more open to authentic expressions of sexuality and gender identity, and with less of the snobbery of the mid-twentieth century. We can fully celebrate the achievements of a man born above a pub in South London, whose sexual desires were illegal for much of his life. While it was necessary for him to present a carefully constructed face to all but a small group of people in his lifetime, we can now appreciate the real Sir Norman Hartnell for the full breadth of his personality and talents.

Matthew Storey

Curator (Collections) Historic Royal Palaces

Sources and further reading

- Jane Hattrick, 'An 'unexpected pearl': gender and performativity in the public and private lives of London couturier Norman Hartnell' in Charlotte Nicklas and Annebella Pollen (eds.) Dress history : new directions in theory and practice (London : Bloomsbury Academic, 2015)

- Amy de la Haye & Edwina Ehrman (eds.), London Couture 1923-1975: British Luxury (London: V&A Publishing, 2015)

- Michael Pick, Norman Hartnell: The Biography (London: Zuleika Books & Publishing, 2019)

- Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasures of the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2005) pp.139-149

- Quentin Crisp, The Naked Civil Servant (first published 1968)

More from our blog

Frances Stuart and Barbara Villiers

10 February 2023

Learn about the relationship between Frances Stuart and Barbara Villiers, two of the most influential women at the court of King Charles II.

The New Constable of the Tower of London

04 October 2022

General Sir Gordon Messenger became the 161st Constable of the Tower of London in August 2022, succeeding General The Lord Nicholas Houghton. The role of the Constable is the most senior appointment at the Tower of London and dates back to the time of William the Conqueror and the Norman Conquest.

A Turkish Bath for Horses at Hampton Court

16 June 2022

With eyes on Royal Ascot in June, we wanted to share a lesser-known aspect of Hampton Court’s Equine Past. In the 1860s a Turkish bath was installed at Hampton Court Palace…for the horses! Buildings Curator Alexandra Stevenson explores this curious history.