The colourful history of the cornices and corbels: Secrets of a State Bed

Date: 06 November 2019

Author:

Beatrice Farmer

As conservation work continues on Queen Caroline's State bed, Conservator Beatrice Farmer describes the small details and considerations involved in conserving the textile elements of the bed such as the cornices and corbels - from how to remove old patches to finding the best materials and colours to match the original item. The bed is part of the Royal Collection, and can usually be found on display at Hampton Court Palace.

The cornices and corbels form the decorative line at the top of the bed around the central structure of the tester. The cornices are fitted along three sides, with the corbels at the corners. They are made of carved pine and covered with silk damask and silk braids, adhered using animal glue.

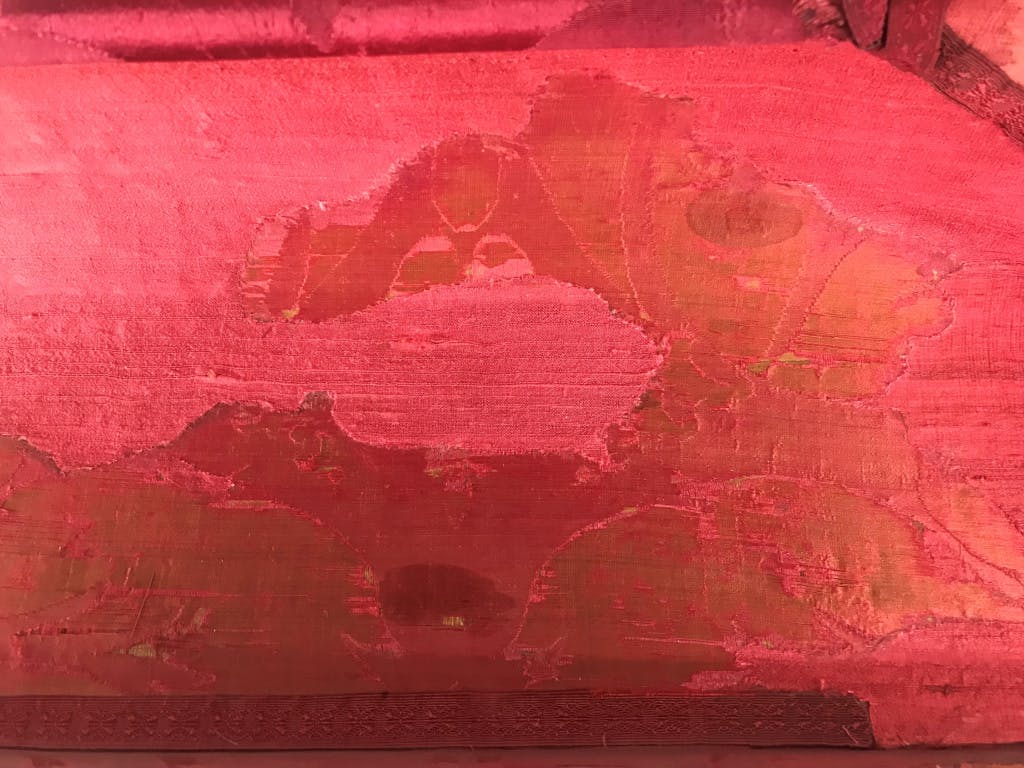

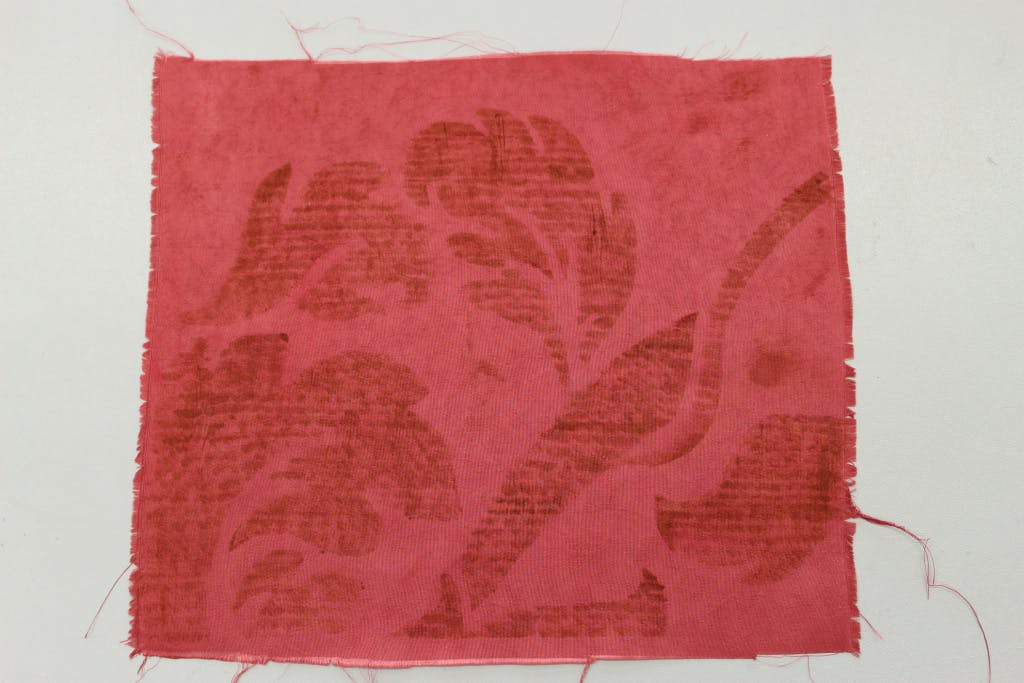

A lot of conservation work involves considering the best approach to take with previous repairs. These repairs are an important part of the bed's history, but our quest is to preserve the original elements of the bed as best as possible, and sometimes this involves undoing and redoing old restorations. Our historic records held here at Hampton Court Palace show that these areas of silk of the corbels and cornices (Fig. 1) were considered too stained and were removed with a scalpel and sandpaper as part of some restoration work completed around 40 years ago. As conservators today we did shudder at the thought. Damask from the original curtains was used to patch some smaller areas. The curtains were so damaged they were considered sacrificial and used as patches across the bed. The large freshly exposed areas here were patched with new dupion silks. The very strange colour is explained in the records- they had quite limited resources so used the best they could, and hoped that the colour would fade with time. Unfortunately. the dye was more light-fast than expected and is still a very bright, incongruous colour. So the history of these changes is quite colourful, using old and new materials.

The quest for authenticity

Today we must ensure authenticity, so we aim to preserve as much of the original as possible and alter as little as we must. The history of these changes to the bed can be seen as evidence of its survival and tell us much about the people who have cared for it over the years, which all must be preserved. However, we need to achieve a coherent look to the bed and a standard finish that reflects the superior quality of the original craftspeople. For the cornices, we have also added the ambition to improve the visual continuity of the damask pattern, due to these large areas of patches which disrupt the design.

Can we remove the patches safely?

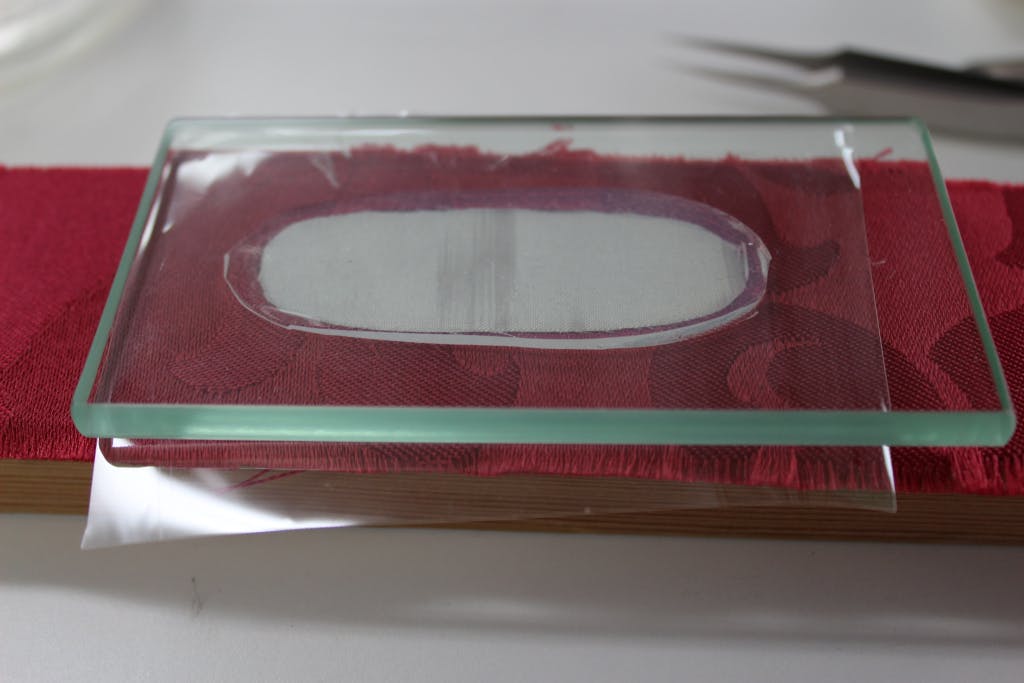

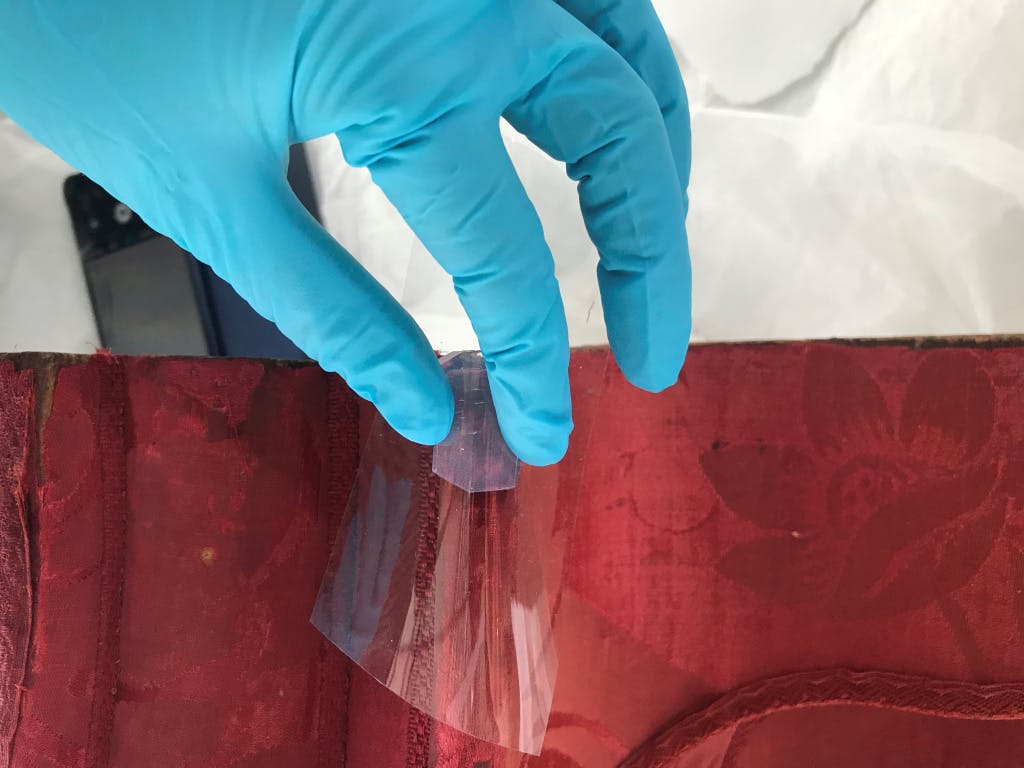

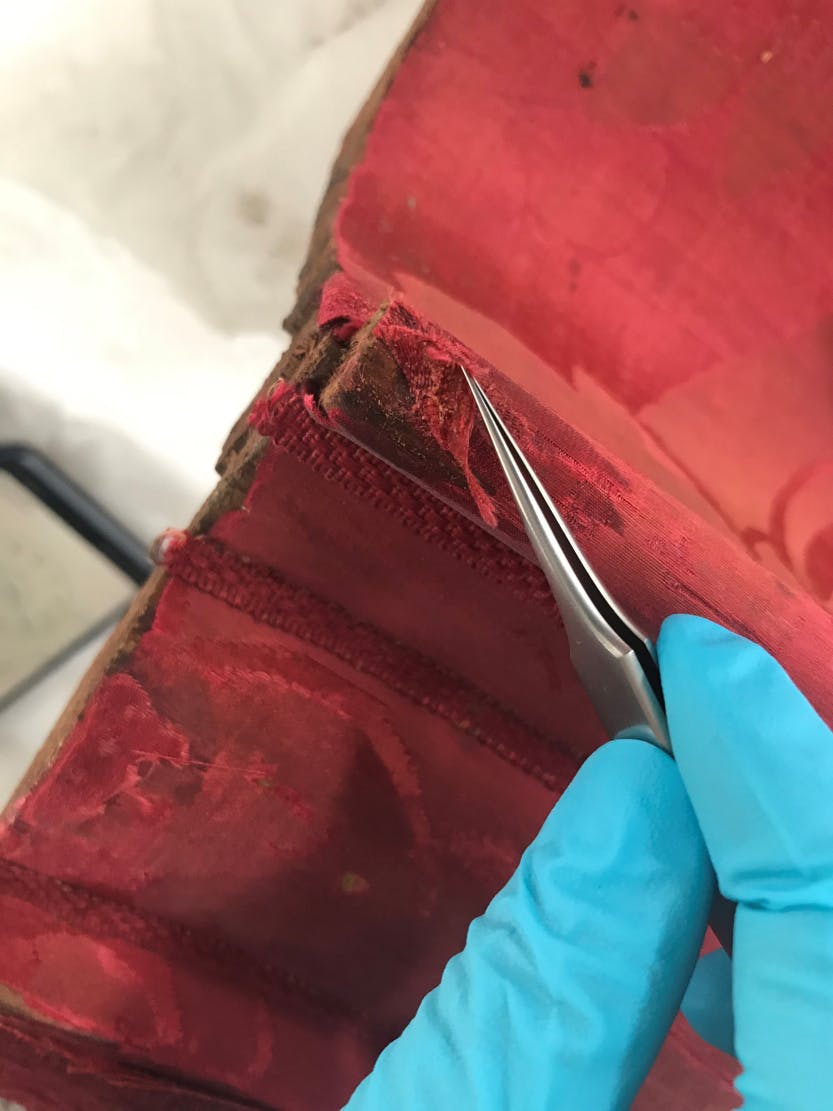

As part of our decision-making process we first needed to see if we were able to remove the patches safely. We made some mock-ups to mimic the original construction by sticking replica silk damask to wooden battens using animal glue. We cut out sections of the damask and then stuck down some new patches using the modern adhesive. We tried a heated spatula first, to raise the temperature and hopefully soften the glue, but this resulted in us tearing off the silk. Fortunately, we had better results using this Agar gel, with some added isopropyl alcohol, and the patch lifted off beautifully without disturbing the original damask. We were then ready to try to remove a real patch on the cornice itself, which also worked really well.

Looking for a damask alternative

Now we knew it was possible to remove the old patches, we needed to see if we could find a better alternative. We used our own existing dye recipes to dye three types of silk to see if it was possible to achieve the variations in colour found on the foot cornice. One recipe which closely matched the colours was selected, and we then painted on the dye to achieve the damask pattern. It was quite a fun and experimental process, using various tools and stippling techniques.

We also tried various types of hand-made paper. Although we had better control to apply the colours evenly, after steaming to fix the dyes, the samples lost their depth of shade and 'sheen' making their appearance less similar to the damask. The option of paper was therefore eliminated at this point.

It was decided that the taffeta was the closest in terms of sheen and drape to that of the original damask and could be the answer. This would allow us to intimate the damask design but it would be obvious on closer inspection that this was not original.

These tests allowed us to find out what was possible, to inform ethical and aesthetic decisions. We will consider these options with the curators, and together decide which of our patches will be best for the overall look of the cornices and the bed as a whole.

Beatrice Farmer

Conservator, Hampton Court Palace

More from our blog

Conservation of an 18th century headboard: Secrets of a State Bed

13 March 2020

As part of our Secrets of a State Bed series, Conservator Viola Nicastro explains the process of conserving the headboard of Queen Caroline's State Bed, and reveals more of its secrets.

Six mattresses for a Queen: Secrets of a State Bed

30 January 2020

As conservation work continues on Queen Caroline's State bed, Conservator Beatrice Farmer shares discoveries on the lavish silk-covered mattresses, including one that appears to be an impostor. The bed is part of the Royal Collection, and can usually be found on display at Hampton Court Palace.

A discovery on the lining: Secrets of A State Bed

08 January 2020

Queen Caroline's state bed has three upper inner valances. These decorative drapes are attached to the inside the wooden bed frame, to hide the bed frame and give a decorative border to the tester or canopy. They are made from silk damask decorated with silk braid and lined with plain silk. Linings are not usually the most exciting or important part of a textile, but these ones turned out to be far more interesting than we thought.