HRP Handover: Zeinab Badawi on Sarah Forbes Bonetta and "contested history"

Date: 22 October 2020

Author:

Zeinab Badawi

Welcome to our second HRP Handover blog for Black History Month 2020. Throughout October we’re inviting independent experts on Black history to present and explore the stories from the past that they’re passionate about.

This week, we’ve invited journalist and Historic Royal Palaces Trustee Zeinab Badawi to share her thoughts on the importance of welcoming diverse perspectives on our past, and the problem with the term ‘contested history’.

Image: Journalist and Historic Royal Palaces Trustee Zeinab Badawi

At last we are having a national - indeed global - conversation about history and heritage. And it is wonderful to see how Historic Royal Palaces has renewed its commitment and is rejuvenating its pledge to build more inclusive storytelling about the palaces under our stewardship. As a member of the HRP Board of Trustees it is exciting to be part of a journey that has received considerable impetus from the current debates about heritage and statues.

This heritage is sometimes described as being ‘contested’, which immediately frames the debate in an oppositional and combative manner. I prefer to see it more as the promotion of the greater knowledge and different insights that come with attention to diverse and inclusive perspectives. It is not a ‘us against them’ set of competing narratives, but a desire to reveal viewpoints that have been obscured, occluded, and even denigrated and which will help reveal a fuller and truer picture of the past. These important viewpoints can then be used to influence our national narrative as an 'outward facing' Britain.

Take the fascinating story of the African Sarah Forbes Bonetta, a protégée of Queen Victoria. Incidentally, Victoria was living in Kensington Palace (one of the six sites cared for by Historic Royal Palaces) when she learned she would become Queen.

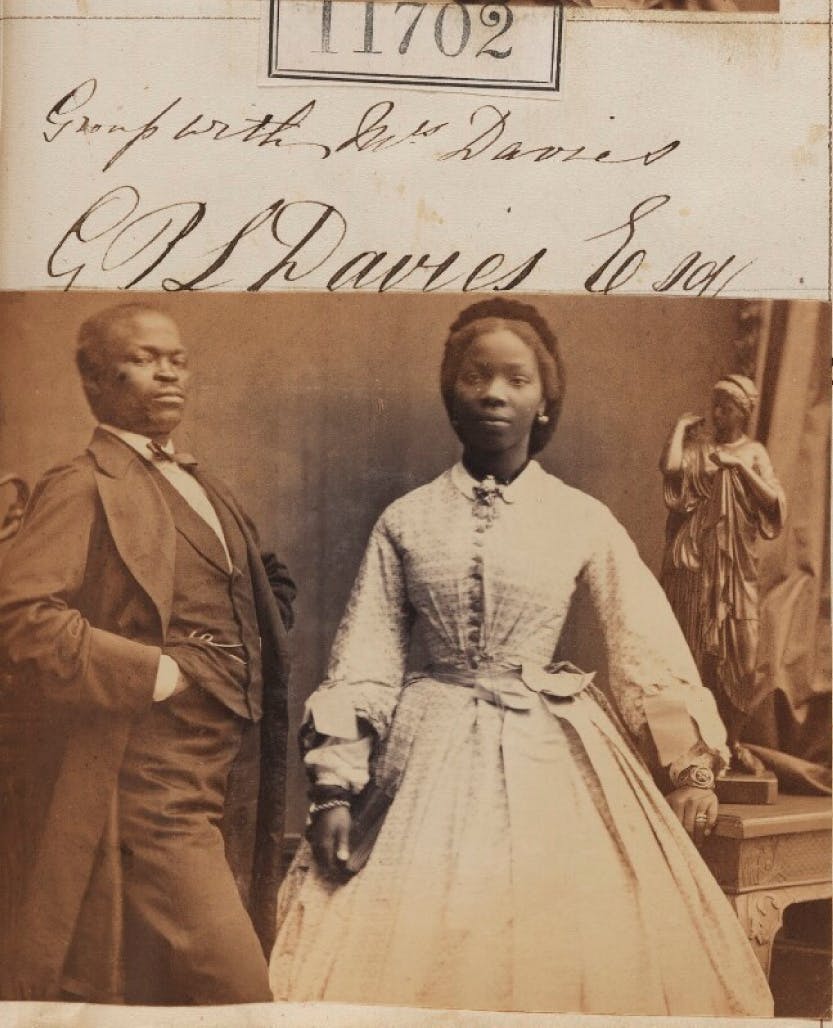

I had come across several photographs of Sarah dated 1862, and was intrigued to see a young African woman dressed in beautiful Victorian clothes and wearing exquisite jewellery. There was also a photo of her with her husband James Davies - who was similarly dressed in fashionable clothing, and their pose suggested they were a couple of high standing. The caption merely stated that Sarah was Queen Victoria's 'god-daughter'. I wanted to know more. But having leafed through every book about Queen Victoria that I could find, I had come across no mention of Sarah Forbes Bonetta in any of them. Further research yielded a unique story and I made a TV documentary for the BBC about her several years ago.

In a nutshell, Sarah had been brought to England as a girl of 6 or 7 by a British captain Frederick Forbes in the 1850s. She was of Yoruba origin and probably came from modern day Nigeria. She was presented to Queen Victoria, who promptly decided to adopt her as her protégée. In this way, Sarah enjoyed a very privileged upbringing: she was an accomplished pianist, was fluent in several languages, and was a regular visitor to the Queen, even enjoying ‘sleepovers’ with the princesses at the palaces and attending their weddings. Indeed when Sarah herself married James, the Queen provided her with a costly trousseau and her wedding ceremony in Brighton included eight African bridesmaids accompanied by eight white ushers. Accounts say that Victorian ‘paparazzi’ were on hand to take photographs of the occasion and there were crowds of curious onlookers - some were even hanging from trees in the church grounds to capture a glimpse of the wedding party.

The story of Sarah and her descendants - some of whom I met in Lagos - is a little-known corner of British history. It speaks of identity and power. It shows how a British monarch, the Empress of many dominions, had an affectionate personal relationship with an African at a time of widespread subjugation and the use of force in the colonies. It shows us how history is complex, varied, intertwined, contradictory, multi-dimensional and above all it tells us that the best and most interesting history is one that includes ALL voices. I am delighted to see that a portrait of Sarah has been unveiled and is now hanging at Osborne House where Queen Victoria used to spend some of her vacations. The palaces that HRP cares for and the people and monarchs who lived in them are a vital part of our history, and it is critical to get the narratives around them right.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta returned to Africa and lived in Lagos, but she remained a regular visitor to London - indeed her first child was named Victoria in honour of the Queen. The little girl was educated at Cheltenham Ladies College at the Queen’s expense, no less. And when Victoria passed a landmark piano exam, the proud Queen reportedly gave all the girls a day off school to mark her achievement.

For those of us with dual heritage - be it British-African/Caribbean, Arab or Asian - seeking an inclusive historic agenda that recognises our voices is not culturally divisive, contentious or ‘cancelling’: it is a desire for recognition that Britain as a past imperial power has been enriched by the experiences of people from its former colonies who are and always have been part of the fabric of this nation, but who for too long have had their accounts and contributions air-brushed from history. We talk of 'Global Britain’ today, but Britain has always been global. And the history of its colonies and their people is an integral part of the story of ALL Britons.

The current debate about Britain's prolific role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade is one glaring example of how the views of Africans and their descendants have not been accorded proper attention. In a recent 20-part TV series about Africa’s history for BBC World TV, I travelled to 32 African countries and interviewed dozens of absolutely brilliant African intellectuals who appear all too rarely on the international public stage; every single one of them pressed for greater global discussion about slavery and other neglected aspects of African history. And we have similar demands today here in the UK for more balanced, honest and inclusive teaching about black history: it is about adding and not 'taking away. The history of Britain's non-white communities informs and has a significant impact on our present in social, political and cultural terms.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta’s relatives in Lagos urged me to make her life story better known. Who can argue against greater knowledge and wider understanding? An ambition to share different views, opinions and perspectives is surely not something to be contested but to be embraced.

Zeinab Badawi

More from our blog

The Life of Edward Francis: Black history at the Tower of London

15 November 2021

Misha Ewen, Curator of Inclusive History, reflects upon her research on the life of Edward Francis - an enslaved African man who lived at the Tower of London in the late 17th century.

Restoring Genius: Grinling Gibbons's Carvings in the Orangery of Kensington Palace

30 July 2021

03 August marks the 300th anniversary of the death of Grinling Gibbons, the greatest woodcarver in British history. Buildings Curator Lee Prosser introduces us to some of his lesser-known but incredibly important works in the Orangery at Kensington Palace.

Queen Anne and Sarah Churchill's last stand off at Kensington Palace

25 February 2021

Holly Marsden, PhD researcher on late-Stuart history, takes us inside Kensington Palace to paint a picture of Queen Anne and Sarah Churchill's final goodbye.