Caring for the Tower of London through lockdown

Date: 11 May 2021

While the Tower of London was closed to the public during the Covid-19 pandemic, much work was underway to protect the fabric of the building and the future of the palace. Assistant Curator Alfred Hawkins reveals one of the important projects that he has been working on behind the scenes.

As a self-funded charity, the closure of the palaces during lockdown has had a devastating financial impact on Historic Royal Palaces. Additionally, being unable to share our spaces and stories with you in person over the past year has been saddening. Our work though, as the custodians of six royal palaces, did not stop when the gates closed. Each of the palaces requires an extraordinary amount of specialist work to maintain and HM Tower of London, as our oldest palace, is no exception. From the White Tower to the moat, a dedicated team has been hard at work behind the scenes maintaining and conserving the palaces in preparation for your return. As we reach the light at the end of the tunnel, I can think of no better time to share what we have been up to.

The Wakefield Tower

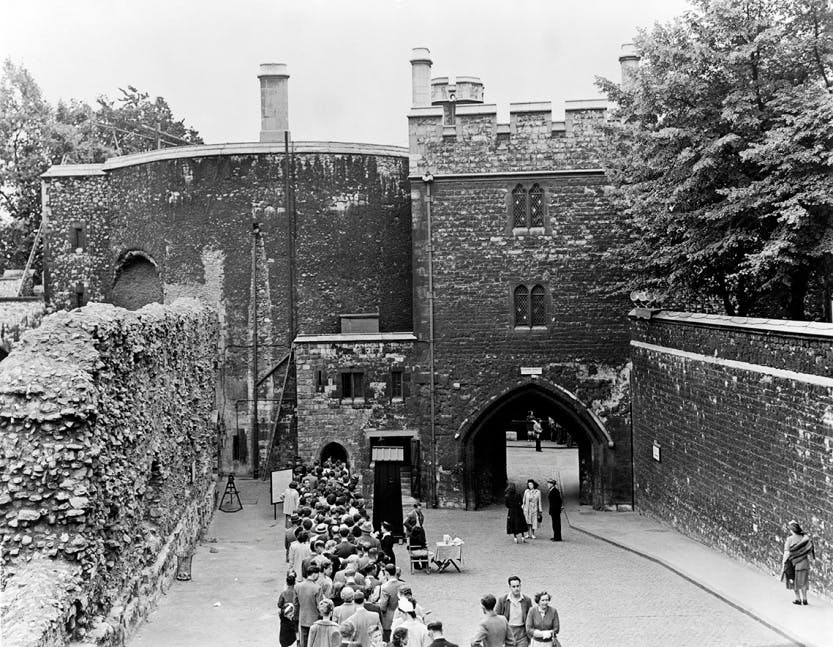

One focus of our work during the lockdown has been the walkways leading to and from the Wakefield Tower (or as it is sometimes known the Torture Tower). The Wakefield Tower itself is a grand example of medieval building prowess, acting as both an extravagant palace and formidable defensive bastion. Built by Henry III between 1220 and 1240, the tower originally sat at the edge of the river Thames and would have been accessible by boat via a postern (a small secondary door) uncovered during excavations in 1957-8.

Following the construction of St Thomas' Tower by Edward I, the Wakefield Tower slowly diminished as a royal lodging, becoming a store for official records from the 14th century until the mid-19th century. After the stores were relocated, the Tower was altered between 1858 and 1869 by architect Anthony Salvin to exhibit the Crown Jewels, which had previously been held in the Martin Tower.

The jewels were held on the first floor of the tower for security reasons and were accessed by an external staircase and, subsequently, a two-storey building which was built against the northern elevation of the Tower. The walkways with which we were concerned, however, have a far shorter and less illustrious history. They were installed in around 1975 following the demolition of the previous entrance in 1970-1 and the relocation of the Crown Jewels to their current home in the Waterloo Block. While the walkways had been altered in 1995 and 2003, the supporting timber beams had never been replaced and were in a poor condition and needed to be replaced.

Now, you’ll be glad to hear that this blog isn’t an attempt to convince you of the importance of 1970s timber walkways. That being said, the removal of the walkways presented us with a unique opportunity to access and record parts of the Wakefield and Bloody Tower which would have usually been inaccessible an opportunity we may not have again for 45 years. This recording, which consisted of a Watching Brief and ˜Stone by Stone’ petrological assessment, was carried out on our behalf by Pre-Construct Archaeology.

Petrology, the study of the formation of rocks, is invaluable to us at the Tower as by observing the microscopic details of a particular stone, alongside how it has been worked, we are able to date any exposed stonework at the fortress (and sometimes even locate the quarry!). This allows us to increase our understanding of the buildings at the Tower and to unravel stories millions of years in the making from the formation, excavation, transport and working of the stones which make up the formidable fortress.

Once the walkways had been removed, the recording process could begin. The first step was to draw the elevations to scale by hand. This drawing was then annotated by a petrologist who assessed each stone individually and took samples in order to ascertain the stone and mortar types, their age and phasing. This leaves an almost undecipherable drawing which forms the basis of our understanding of that particular section of the wall. Finally some computer magic converted those drawings into a scaled digital image accompanied by a report on the stone and mortar types present.

Image: The southern walkways blocked access to many historic features which required our attention, including this medieval drain which was fully recorded following the removal of the walkway. © Historic Royal Palaces

Through this assessment, the elevation shown above can be dated to around the 13th century. It contains a large quantity of Kentish Ragstone, a common building material at the Tower, alongside more unique pieces of Caen stone from Normandy, large quantities of which had been used by William the Conqueror in the construction of the White Tower. Alongside these were a number of re-used worked Roman stones which had almost certainly formed part of the city walls of Londinium almost two thousand years ago. Through combining these results with previous excavations, we can interpret this as a revetment (supporting) wall related to a defensive ditch dug around the Tower during Henry III's works to expand the fortress.

Image: The new southern walkways exiting the Wakefield Tower. © Historic Royal Palaces

Recording these previously concealed features helps to increase our understanding of the development of the Tower of London from William the Conqueror’s great keep to the sprawling fortress we know today, but this is by no means their only purpose. One of the most important aspects of the archaeological process is the creation of a 'permanent record’. They provide us with a safeguard if, touch wood, a section of wall was to collapse and be lost to us forever.

This important work, which helps us to record and understand the secrets of the Tower, can only be undertaken with the support of every member, visitor or donor who allows us, as an independent charity, to fund the continued maintenance of our irreplaceable palaces.

Do pay us a visit and keep an eye out for the extraordinary features that you have helped to preserve. And from everyone here at Historic Royal Palaces - thank you.

Alfred Hawkins

Assistant Curator, Buildings HM Tower of London

More from our blog

Anthony Salvin: the architect who transformed the Tower of London

16 December 2021

Archivist Tom Drysdale introduces Anthony Salvin, the Victorian architect who began the transformation of the Tower of London, and looks at four drawings that shed a light on his work and legacy.

A Short History of the Jewel House at the Tower of London

11 December 2023

Tom Drysdale, Archivist and Curator of Architectural Drawings at the Tower of London, explores the fascinating history of the world-famous Crown Jewels exhibition.

Restoring Genius: Grinling Gibbons's Carvings in the Orangery of Kensington Palace

30 July 2021

03 August marks the 300th anniversary of the death of Grinling Gibbons, the greatest woodcarver in British history. Buildings Curator Lee Prosser introduces us to some of his lesser-known but incredibly important works in the Orangery at Kensington Palace.