With eyes on Royal Ascot this week we wanted to share a lesser-known aspect of Hampton Court’s Equine Past. In the 1860s a Turkish bath was installed at Hampton Court Palace... for the horses! Buildings Curator Alexandra Stevenson explores this curious history.

Recently, as I was doing a little research, I came across one interesting account off-topic that indicated that a Turkish bath for horses was to be installed at the palace in the 1860s. Just the one small paragraph and little else to go on, it was enough to spark my interest...

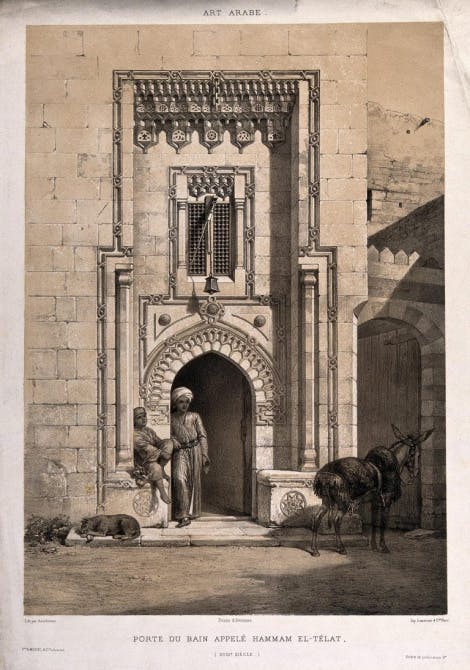

Image: The doorway to the Turkish bath, El-Télet, Cairo, Egypt. Lithograph by L.A. Asselineau after A.C.T.E. Prisse d’Avennes, in L’Art Arabe, 4 vols 1869-1877 © Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), Wellcome Collection.

Origins of the Turkish bath

The first stop was to think about how Turkish baths came into being in the 19th century. If we briefly travel back a couple of millennia, their concept and architecture essentially stem from the Roman balnea, that made their first appearance in around the 2nd century BC.

We’re all familiar with the lavishness of the Roman baths, but whilst in the British Isles they disappeared more or less with the end of Roman rule in the 5th century AD, they continued to be a strong feature of cultural and spiritual life in the Maghreb, the Middle East and much of the Mediterranean basin, for centuries.

More accurately Known as the Hammam (Arabic for hot water), not unlike the Roman baths, they traditionally comprised of a warm room, hot room, and steam room with dressing rooms and areas for massage relaxation and refreshment. Not unlike the spa you might treat yourself to today.

Turkish baths in Britain

Whilst there were some public baths in Britain during the Medieval and early Modern Periods known as Stews where some could enjoy bathing and other rather less salubrious pursuits, they unlikely had the physical and mental therapeutic benefits of the Turkish bath. It wasn’t really until the mid-19th century that hot-dry air baths became fashionable, and most importantly open to all sectors of society.

The Turkish bath or Hammam, was ‘re-discovered’ by David Urquart, a 19th-century diplomat and politician who enthusiastically advocated their benefits in his travel book, The Pillars of Hercules (1850). John Balbirnie, a Scottish physician, sung their praises too in 1863: “It may be affirmed that the Turkish Bath amounts almost to a discovery! It is at least a new found boon to the States of the Western World.[1]” Alongside the new Victorian gusto for hydropathy and preventive medicine, The Turkish bath was a foreign tradition that would help raise the Victorian ideas of personal hygiene.

Health benefits

Inspired by Urquhart’s enthusiastic description of Turkish baths in his book, the Irish physician Dr Richard Barter (1802-70) opened the first Victorian Turkish bath, or more accurately Roman-Irish bath, in County Cork in 1856 [2]. The concept rapidly made its way across the Irish sea to the industrialised zones of the north of England, journeying up to Scotland and even as far as Australia before the first Turkish baths ever graced the London scene four years later in 1860.

The Victorian Turkish bath became increasingly popular, used by a wide sector of society for sanitary as well as curative use. The dry heat of the Victorian Turkish bath, although not a cure-all as some claimed, did prove to help with certain ailments such as rheumatism and ‘affections of the lungs’, and so attention soon turned to the hard-working four-legged creatures of Victorian life.

Hydrotherapy for animals

It was widely believed that what was good for humans might also be good for animals. With the success of Dr Barter’s Turkish bath at his hydropathic establishment in St Ann’s, which had its own farm to provide fresh produce for his patients, it naturally followed that he built one for his farm animals in the 1850s. He used the baths for sick cattle, pigs, horses and dogs.

It was such a success that similar baths were soon built on nearby farms, bearing in mind this was before London had a Turkish bath for people!

On mainland Britain, initial interest in the Turkish baths for animals was directed at improving the stamina of racehorses, but by the 1860’s veterinarians were becoming interested in the therapeutic effects on urban workhorses as well as farm animals. It’s not such a ludicrous idea when you think how important horses were in the 19th century, particularly with the development of the railways.

The Great Northern Railway Company owned facilities that cared for their horses, including at their hospital for horses in Totteridge, whilst Pickfords the Carriers built a Turkish bath for horses at their Finchley Depot. The horses were treated to a suite of three interconnected rooms undergoing sweating, washing and drying.

Horse bathing at Hampton Court

There were other smaller facilities of course and veterinarians the land over were keen to try it out for themselves. William Joseph Goodwin, who served as personal veterinarian surgeon to Queen Victoria, appears to have taken a keen interest in the therapeutic potential of Turkish baths on horses. Goodwin lived at Hampton Court Palace in a large apartment conveniently located at the Royal Mews on Hampton Court Green [3].

On the 21st January 1861, he requested permission to construct a Turkish bath in a portion of an unoccupied stable in the Royal Mews, to “test the effect of Turkish Baths on horses [4]”. His request was quickly approved nine days later by the Vice Chamberlain on condition that the work was done at Goodwin’s expense under the supervision of the Surveyor of Works and that he would remove the fittings whenever the Board of Works required him to do so.

It’s interesting that Goodwin appears to have had no trouble in getting approval for what might have been viewed as a rather frivolous pursuit, especially when you consider the below par living conditions of the some of the Grace and Favour apartments at the palace. Many residents fought to have some form of washing facility installed in their antiquated apartments but usually to no avail. The treasury invariably refused on the grounds that bathrooms could only be installed at public expense upon a change of occupant.

One such occupant, Millicent Gordon who lived in the palace for 100 years, made one last plea to have a bath installed at the age of 97. The best and presumably cheapest solution appears to have been that a bath could be installed in her kitchen – a world away from the luxury of a Turkish bath. The Housekeeper tried to fight for this longstanding resident and said “She doesn’t want it in her kitchen, as it will interfere with her cooking arrangements [5]”. Millicent sadly died three years later sans bath.

Henry VIII’s Baths at Hampton Court and Whitehall

Not everyone at Hampton Court suffered from a lack of bathing facilities of course, and the Horse Hammam was not the first spa-like bathing area at the Royal palaces. Henry VIII had no trouble procuring a bathroom, luxuriating in his lavishly decorated private bathroom on the 1st floor of the Bayne Tower at Hampton Court, (b.1529).

More magnificent still, and perhaps approaching the indulgence of a Turkish bath was his later sunken pool at Whitehall Palace (1540s), inspired by Francis I’s bathroom suite of 6 rooms at Fontainebleau. During excavations in the 1930s at the lost palace of Whitehall, evidence was found of a sunken bath, together with fragments of elaborately decorated green-glaze stove tiles.

Alongside furniture listings that included trussing beds in bathrooms at others of Henry’s homes such as at Greenwich Palace – these luxurious hot and cold pools certainly bring to mind the decadence of the Roman baths.

I've yet to find any evidence for what the Turkish bath for horses looked like at Hampton Court, but I continue to search the archives for possible clues whenever I have the chance!

Author: Alexandra Stevenson,

Assistant Curator, Archaeology and Buildings.

1. In: Adams, G,F ed. (1881). Turkish Bath Handbook. St. Louis: Little & Becker.

2. Shifrin, M., (2015). Victorian Turkish Baths. Historic England.

3. Pro/Work 19/14/2.

4. Pro/Work/1/67.

5. Parker, S,E. (2005). Grace & Favour. A Handbook of Who Lived Where in Hampton Court Palace 1750-1950. Historic Royal Palaces. Hampton Court Palace.

More from our blog

The Wedding of Captain Scott and Kathleen Bruce at Hampton Court Palace

04 January 2024

Assistant Curator Minette Butler explores how Captain Scott's wedding to his beloved wife Kathleen Bruce at Hampton Court Palace intertwines with the aftermath of his ill-fated expedition to reach the South Pole.

Sir Christopher Wren's Hampton Court Palace

08 March 2023

Head of Historic Buildings Daniel Jackson looks at one of Sir Christopher Wren's most famous and problematic projects: the remodelling of Hampton Court Palace.

A Short History of the Jewel House at the Tower of London

11 December 2023

Tom Drysdale, Archivist and Curator of Architectural Drawings at the Tower of London, explores the fascinating history of the world-famous Crown Jewels exhibition.