A revolutionary building. Spectacular paintings. Royal execution site.

Banqueting House is a magnificent survivor of the lost royal Palace of Whitehall.

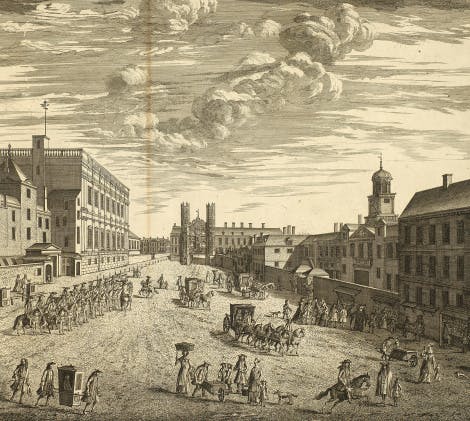

Image: View of the Palace of Whitehall in 1724 (detail), Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017.

Palace of Whitehall

The great Palace of Whitehall began as the medieval London home of the Archbishops of York, and was known as York Place. The once mighty Cardinal Wolsey, also Archbishop of York, fell foul of Henry VIII, and his London home was taken from him.

Henry set about enlarging York Place, and transforming it into a magnificent royal palace, fit for himself and his Queen, Anne Boleyn. He called it Whitehall, and it became the principal setting for the passions, intrigues and ceremonies of the Tudor, and afterwards, the Stuart monarchies. In 1698, disaster struck - the palace burnt down.

Early banqueting houses

The Banqueting House we see today had two predecessors. Elizabeth I was wooed by her noble suitors in the first building, meant to be temporary, which was made of bricks, timber and canvas, with a ceiling beautifully painted with vines and fruit – all symbols of the hoped-for fecundity of a marriage which never materialised.

Despite its flimsy construction, this old banqueting house was much in demand from Elizabeth’s successor as a venue for masques. James I and his wife Anne of Denmark loved this form of extravagant performance. Eventually James commissioned a more substantial hall from architect Robert Stickells. However, the King was disappointed with the building. Although very ornate, a forest of columns supporting a gallery blocked much of the audiences’ view.

Did you know?

Stickell’s banqueting house burned down in 1619 after scenery caught fire. The King was not at all sorry.

Image: Inigo Jones after Sir Anthony van Dyck. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Inigo Jones's Banqueting House

James’s new Surveyor of the Kings Works, Inigo Jones, was chosen to build the third, and final, Banqueting House. Son of a London carpenter, Jones was a skilled costume and scenery designer, as well as a gifted architect. Together with the playwright Ben Jonson, he had created many wonderful masques for Queen Anne.

Inigo Jones knew of the King’s disappointment with his previous building, so he drew up plans for a completely different, classical building. Jones had travelled widely in France and Italy, where he made copious notes and drawings of the architecture of ancient Rome and the Renaissance. Inspired by the classical forms he encountered on his travels, he adapted elements of the buildings he had witnessed, and reinterpreted them in a new and unique way, to suit his royal patrons.

His spectacular Banqueting House building was completed in 1622, to the King’s great delight and the astonishment of all who surveyed it.

Image: Great Hall at Banqueting House. © Historic Royal Palaces

Perfectly proportioned

Jones’s Banqueting House has an enormous hall, with the dimensions of a double cube, resting on top of a vaulted Undercroft.

The spectacular carved and gilded ceiling now contains the nine paintings by Rubens, which were installed in 1636.

The ceiling was painted a plain white before Rubens' paintings were installed, but was darkened with 'walnut-tree' colour and richly gilded after their installation.

Image: Banqueting House exterior. © Historic Royal Palaces

The Banqueting House exterior

The building’s exterior was originally more colourful than today, as it was made with alternating honey-coloured and pinkish-brown stone, with other decorative features in white Portland stone.

Today the facade is a monochrome greyish-white, as it was partially refaced with Portland stone in 1774, and then entirely, in a large-scale restoration by John Soane, starting in 1829.

Image: Rubens ceiling at Banqueting House. © Historic Royal Palaces. Image by Google.

Rubens and the Banqueting House

The crowning glory of the Banqueting House is its magnificent nine ceiling paintings by Peter Paul Rubens – one of Europe’s most influential and important artists.

These vast oil-on-canvas paintings are unique, in that they remain in the very ceiling for which they were first painted – most of Rubens’s paintings are in art galleries around the world.

Image: Charles I on Horseback by Sir Anthony van Dyck, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017.

The paintings in place

James I began discussions with Rubens about a decorative scheme for the Banqueting House, but it was his son, Charles I who finally commissioned the paintings.

Rubens presented Charles with working sketches, but painted the finished canvases in Antwerp.

They were installed in 1636, and Rubens was paid (rather belatedly) £3000 and given a gold chain for his services.

The paintings glorify the achievements of his father, and depict James as a divine figure – the implication being that his Stuart heirs were too.

Image: Detail of one of the paintings, The Union of the Crowns by Peter Paul Rubens. The goddess Minerva brings together the two crowns of Scotland and England over the head of a young child, who may represent Great Britain and the future Charles II, grandson of James I. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017.

Reading the ceiling

The three largest paintings depict James uniting the thrones of Scotland and England, ruling his land wisely, like Solomon, and ascending into the heavens, transported by classical gods and goddesses.

Royal healing ceremony

Since the Middle Ages, English monarchs had claimed to have the power to heal, or at least prevent, ‘the King’s Evil’. It’s not clear exactly what this nasty skin disorder was, possibly leprosy, or scrofula, which causes large growths on face and neck. It became known as ‘the Kings Evil’, alluding to the belief that sufferers would be cured by the touch of the monarch.

James I decided to use his fabulous new Banqueting House to stage this mystical ritual of monarchy, which was continued by Charles I. Revived by his son Charles II in 1661, the ritual became wildly popular.

Did you know?

In the first six months after the Restoration of the Monarchy, Charles II used the Banqueting House to touch over 7000 sufferers!

Image: Samuel Johnson by Sir Joshua Reynolds, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Johnson's angel

Queen Anne (1702-14) however was the last monarch to perform the ceremony as George I thought it ‘too Catholic’.

Writer Samuel Johnson remembered going to the Banqueting House as a child to be touched by the Queen. He described her as ‘a lady in diamonds and a long black hood’.

Everyone who came to be healed was given a token known as an ‘angel’. Johnson wore his angel for the rest of his life.

Image: Portrait of John Evelyn by Robert Walker. © National Portrait Gallery, London

His Majesty sitting under his state in the Banqueting House, the chirurgeons caused the sick to be brought, or led, up to the throne … the King strokes their faces or cheeks...

Diarist Sir John Evelyn, 1660, describing a healing ceremony.

Image: German print depicting the execution of King Charles I in 1649. © Historic Royal Palaces

Execution site

Just 13 years after Rubens’ canvas were installed Charles I viewed the ceiling for the last time, as a condemned man.

The irony of the divine right of kings cannot have been lost on him as he walked to his death under the magnificent canvases: commissioned as a tribute to his father.

The King was executed on a specially built scaffold outside the Banqueting House on 30 January 1649.

His death is commemorated in a special service held there every year on the anniversary.

The Royal Maundy

Distributing money to the poor on the Thursday before Easter is a long-standing Christian royal tradition. Monarchs from Charles II to Queen Victoria frequently used the Banqueting House for this special ceremony, which evoked the way Jesus took the role of the lowliest servant and washed the feet of his disciples at the Last Supper.

As well as distributing cash, food and clothing, the monarch was also expected to wash the feet of the paupers who approached them. However, this wasn’t really an unpleasant task, as a royal official ensured that the chosen paupers’ feet were very well scrubbed in advance!

Did you know?

The Banqueting House was last used for Royal Maunday in 1890, when Queen Victoria distributed alms.

Image: The Distribution of Royal Maundy in the Chapel Royal, Whitehall.

Today's Maundy

The ritual of foot washing was abandoned in the 18th century. However, to this day, the Lord High Almoner still traditionally carries a towel over his right shoulder during the Maundy service.

Browse more history and stories

The execution of Charles I

Killing of a 'treasonous' King

The masque

A fabulously extravagant early 17th century court entertainment

The Rubens ceiling

The crowning glory of the Banqueting House

Explore what's on

- For members

- Events

Members-Only Days at Banqueting House

Explore the Banqueting House, Whitehall on this exclusive members-only day after its temporary closure. Learn all about this iconic building and its rich history.

-

26 February, 21 March, 10 April, 02 May, 28 May, 27 June

- 10:00 - 16:00 (last entry at 15:00)

- Banqueting House

- Separate ticket (advance booking required)

- Things to see

The Undercroft

Explore the vaulted drinking den beneath the Banqueting House, which was used by James I and VI for decadent royal parties.

- Banqueting House

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Banqueting Hall

Experience James I and VI's breathtaking Banqueting Hall, created in 1622 as a venue for extravagant Jacobean entertainments.

- Banqueting House

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)