Killing of a 'treasonous' King

As a King, Charles I was disastrous; as a man, he faced his death with courage and dignity. His trial and execution were the first of their kind.

Charles I only became heir when his brother Henry died in 1612. Charles had many admirable personal qualities, but he was painfully shy and insecure. He also lacked the charisma and vision essential for leadership. His stubborn refusal to compromise over power-sharing finally ignited civil war.

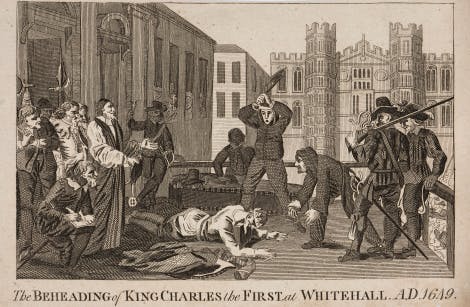

Seven years of fighting between Charles’ supporters and Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarians claimed the lives of thousands, and ultimately, of the King himself. Charles was convicted of treason and executed on 30 January 1649 outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall.

Did you know?

Charles was not born to be king. He was the youngest child of James I, known as ‘Baby Charles’.

Image: Charles I circa 1616, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Birth of Charles I

Charles was born on 19 November 1600 at Dunfermline Castle in Fife, Scotland. He was the second son of James VI of Scotland/James I of England and the youngest of the royal family.

If Charles’ popular and likeable elder brother Henry had not died young of typhoid it is unlikely that England would have been riven by the bloodiest civil war ever known.

Charles was a sickly child, very small (his adult height was only 1.5m) and still could not walk or talk aged two.

He inherited his father’s lack of confidence and a slight speech impediment, which he worked hard to conquer.

When his father succeeded to the English throne in 1603 the family moved to London. Two-year-old Charles spent his first English Christmas at Hampton Court Palace.

Image: Charles I with Henrietta Maria, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Marriage to Henrietta Maria

Charles was crowned on 2 February 1626, aged 25. He had married Henrietta Maria of France the previous year. The royal marriage produced nine children, including future Charles II, and Mary Henrietta, who married William II of Orange.

Image: King Charles I by Gerrit van Honthorst, 1628, © National Portrait Gallery, London

A controversial King

Charles I's troubled leadership

In private, Charles was gentle and polite, by all accounts a loving father. However, in public the King’s acute shyness made him appear haughty and arrogant.

Charles also did not allow anyone except his wife to sit in his presence. This infuriated his enemies, particularly Parliamentarians.

His lack of empathy and refusal to consider opposing views led to his increasing unpopularity. Determined to maintain absolute power, Charles was out of step with the changing times.

Image: Detail from The Apotheosis of James I c. 1632-4 by Sir Peter Paul Rubens. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The Divine Right of Kings

Charles I's absolute monarchy and divine right

Charles inherited his father’s belief in the Divine Right of Kings, a doctrine upheld by the entire Stuart dynasty, one of the most powerful families ever to have ruled Scotland.

They believed that kings were chosen by God to rule, and that only God could overrule them.

Charles also believed that he had the sole right to make laws, so to oppose him was a sin against God.

He genuinely believed that a dictatorship was the only effective form of government.

The magnificent Rubens ceiling painting at the Banqueting House, completed in 1636, was commissioned by Charles to celebrate these divine principles.

In this detail of the main canvas, The Apotheosis of James I, his father is portrayed ascending to heaven in a cloud of glory.

Story: Secrets of the Banqueting House

Read about the execution of Charles I in the Secrets of the Banqueting House story on Google Arts & Culture.

A king defeated

The Royalist defeat and Oliver Cromwell's rising power

The Royalists made a strong start, and their cavalry remained undefeated until 1644. Gradually the Parliamentarians under military genius Oliver Cromwell began to gain the upper hand in what became the bloodiest war ever fought on English soil.

The Battle of Naseby in June 1645 and the defeat of the Royalist army probably marked the turning point in the war, although fighting dragged on until 1649.

Did you know?

Some families had bitterly divided loyalties, brother fighting brother, but religion cut deeper, with Catholics tending to support the King.

Image: The Kitchen Garden at Hampton Court Palace. © Historic Royal Palaces

Charles I imprisoned

The King's refusal to surrender

In 1647 Charles was imprisoned by Cromwell and put under house arrest in the old Tudor royal apartments at Hampton Court Palace (pictured), from where he famously escaped. He was soon recaptured and kept prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, where he was well-treated.

But despite many opportunities, Charles refused to repent and seek a negotiated peace. He stubbornly refused to accept defeat or submit to the republican authority.

Sad farewells

King Charles' heartbreaking goodbye to his children

Charles I was given just three days to put his affairs in order and say goodbye to his family. After the trial he was taken by sedan chair a short distance to his old room at Whitehall Palace. Charles refused to see anyone but his children and his chaplain, Bishop Juxon. The next day the King was moved to St James’s Palace.

Charles spent the day burning papers, praying and saying sad farewells to his two youngest children, Henry Duke of Gloucester, aged 9 and Princess Elizabeth, who was 11.

Did you know?

His wife, Henrietta Maria had fled abroad earlier in the war, and his other children were also in exile.

Image: Five eldest children of Charles I - Mary, James II, Charles II, Elizabeth and Anne. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

A father's last words

The King told his two youngest not to grieve, that they should obey their elder brother Charles, the lawful sovereign.

Elizabeth cried hysterically when she realised she should not see her father again, and he hid his own tears to calm her.

Image: King Charles I after Sir Anthony van Dyck. © National Portrait Gallery, London

‘Sweetheart, you will forget this.’

Charles consoling his daughter Elizabeth. She recorded every detail in her diary that evening.

Image: The Great Hall in the Banqueting House. © Historic Royal Palaces

Prayers and preparation

Charles I's dignified preparation for death

The following morning, Tuesday 30 January, the King rose early and dressed for the icy weather, asking for a thicker-than-normal shirt, so that he wouldn’t shiver, and people wouldn't think he was quaking with fear.

He then retired with Bishop Juxon to pray until a knock came on the door at 10am.

Charles, the Bishop and his attendant Thomas Herbert walked across St James’s Park, the King wrapped in a black cloak, surrounded on all sides by guards.

The King was taken to his bedchamber in Whitehall Palace, to await summons to the scaffold. This came three hours later.

Charles walked across the floor of Banqueting House, beneath the Rubens ceiling painting; 20 years before, he had commissioned this magnificent ceiling from Rubens.

A bitter day

A huge crowd had gathered in the bitter weather. But they were held so far away that the King's final short speech was lost in the freezing air. Erected against the Banqueting House in Whitehall, the scaffold was hung round with black cloth.

In the centre of the blackened and sanded floor stood the axe and a lower quartering block of a kind used to dismember traitors. Two men, heavily disguised with masks, stood ready to perform the act.

Did you know?

It is said that Brandon, the official executioner could not be found.

The death of a king

The final seconds of Charles I's life

The King, his hair now bound in a white nightcap, took off his cloak and laid down. He told the executioner that he would say a short prayer, and then give a signal that he was ready.

After a little pause, the King stretched out his hand, and the axe fell, the executioner severing his head in one clean blow.

Image: Charles I by Anthony van Dyck. Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2017

I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown; where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world.

Charles I, minutes before the executioner's axe fell.

Image: The Execution of Charles I, © National Galleries of Scotland. By permission of Lord Dalmeny.

A horrifying deed

Many watching were aghast, with one witness commenting 'There was such a groan by the thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again’.

Return of a king

Charles II and the restoration of royal power

When Charles II returned from exile in 1660, public opinion had swung right back behind the monarchy. Many people were heartily sick of the sober restraints of Puritanism.

Oliver Cromwell, who died a disillusioned man in 1658, had failed to create a working Parliament and his incompetent son and heir, Richard, was forced to resign. Rather than endure another Civil War, Parliament invited the late King’s son to return to rule.

Did you know?

Oliver Cromwell's son was known as ‘Tumbledown Dick’.

Image: King Charles II, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

Charles II's decisive action against Republicans

Under Charles II, the surviving 41 republicans who had signed the death warrant were called to account. Most fled abroad, or surrendered voluntarily to avoid execution.

The 10 men who refused to beg forgiveness were tried and sentenced to death.

After Restoration, royalists dug up Oliver Cromwell's rotting corpse and hanged it at Tyburn.

Image: Bust of King Charles I outside Banqueting House. The inscription reads: 'His majesty King Charles I passed through this hall and out of a window nearly over this tablet to the scaffold in Whitehall where he was beheaded on 30th January 1649'.

A beautiful legacy

Charles I's enduring impact and art collection

Charles I remains the only English monarch to have been tried and executed for treason.

In the years after his death, the muddle of Parliament, sober life under the Puritans and ultimately failure to establish a functioning government meant people started viewing Charles I differently.

Perhaps Charles I's most important legacy is his fabulous art collection, which now forms the Royal Collection.

The execution of Charles I is remembered every year on 30 January with a service in the Banqueting House.

Image: This Anthony van Dyck painting at Hampton Court Palace, dated to around 1637, shows Charles I's daughter Princess Mary at the age of five or six. © Historic Royal Palaces

Patron of the arts

Despite his crucial failings as a monarch, Charles was a true patron of the arts. In addition to acquiring a personal collection of some 1,400 paintings and 400 pieces of sculpture, he also patronised and encouraged the leading artists and architects of the day.

Watch The Execution of Charles I: Killing a King

On the 30th January 1649, King Charles I was executed outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall. His trial was a momentous event in British history.

He was found guilty of treason - a ‘tyrant, traitor, murderer and Public Enemy’. What led to this unprecedented killing of a king?

This content is hosted on YouTube

This content may be using cookies and other technologies for which we need your consent before loading. To view the content, you need to enable cookies for "Targeting Cookies & Other Technologies".

Manage CookiesVideo Transcript of The Execution of Charles I: Killing a King

Follow along with an interactive transcript of The Execution of Charles I: Killing a King on YouTube. A link to open the transcript can be found in the description.

Browse more history and stories

The story of Banqueting House

Four hundred years of history and the site of a royal execution

The masque

A fabulously extravagant early 17th century court entertainment

The Rubens ceiling

The crowning glory of the Banqueting House

Explore what's on

- For members

- Events

Members-Only Days at Banqueting House

Explore the Banqueting House, Whitehall on this exclusive members-only day after its temporary closure. Learn all about this iconic building and its rich history.

-

26 February, 21 March, 10 April, 02 May, 28 May, 27 June

- 10:00 - 16:00 (last entry at 15:00)

- Banqueting House

- Separate ticket (advance booking required)

- Things to see

The Undercroft

Explore the vaulted drinking den beneath the Banqueting House, which was used by James I and VI for decadent royal parties.

- Banqueting House

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Banqueting Hall

Experience James I and VI's breathtaking Banqueting Hall, created in 1622 as a venue for extravagant Jacobean entertainments.

- Banqueting House

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

Shop online

Charles I Dated Decoration

This exclusive decoration has been created to commemorate the reign of Charles I who ascended the throne 400 years ago.

£50.00

Official Banqueting House Guidebook

Descriptive, informative, authoritative - this superb guidebook is the best way to learn all there is about Banqueting House.

£4.99

Shop Banqueting House

Discover our wonderful collection of gifts and souvenirs inspired by Banqueting House.

From £4.50