The terrible fire that destroyed one of Europe’s finest palaces

At the time of its fiery destruction in 1698, Whitehall Palace was probably the largest palace in Europe; the centre of English royal power for 168 years. The fabulous palace was created by Cardinal Wolsey as his central London residence. It was enlarged and extended massively by Henry VIII after 1530.

Whitehall was at the centre of some of the most momentous events in English history, from the execution of Charles I in 1649 to the Glorious Revolution and succession to the throne of William III and Mary II in 1689-90.

The Lost Palace of Whitehall

Whitehall Palace began life as York Place, the Westminster house of Cardinal Wolsey.

Henry VIII appropriated this desirable residence in 1530 on Wolsey’s fall from grace, and made it his own, turning it into the most magnificent palace in Britain.

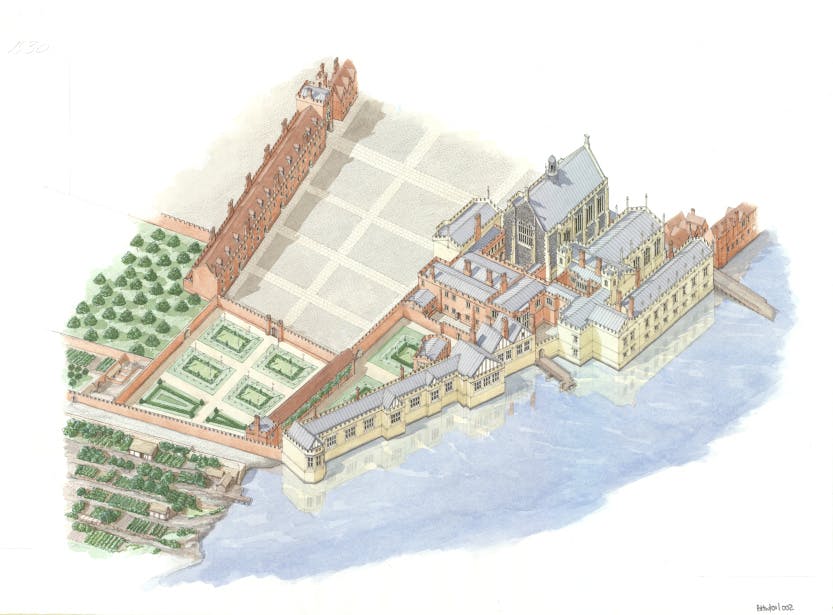

Image: Reconstruction of York Place, Whitehall in 1530. This drawing shows York Place at its largest extent, on the eve of Wolsey's fall.

Power palace

It began to be known as ‘Whitehall’ throughout Europe as the name of the palace of the kings and queens of England. This forged the link between Whitehall and the power of the state – a link which remains to this day.

Image: The Family of Henry VIII (detail) by an unknown painter, c1545 was possibly set within the splendid interior of Whitehall Palace.

A place that fills one with wonder... because of the magnificence of its bedchambers and living rooms, which are furnished with the most gorgeous splendour.

Baron Wildstein, a Moravian aristocrat visiting Whitehall in the early 1600s.

Story: Secrets of the Banqueting House

Discover the devastating impact of the Whitehall Fire of 1968 in the Secrets of the Banqueting House story on Google Arts & Culture.

Life on the river

This painting shows Whitehall Palace at its greatest, stretching along the banks of the Thames. Palace inhabitants enjoyed a fabulous view of river pageants such as this one.

Image: The Lord Mayor's Water-Procession on the Thames c1683, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017 (Detail version in header image)

The fire starts

On the afternoon of 4 January 1698, a Dutch maidservant was drying linen sheets on a charcoal brazier in a bed chamber at Whitehall Palace.

This was usual practice, but it was forbidden to leave braziers unattended. However, the maid left the room.

It only took a second for the sheets to ignite, then to set fire to the bed hangings, and then the whole lodging was ablaze.

Did you know?

Gunpowder was used to try to prevent the flames from spreading by blowing up buildings to create a firebreak.

Fuel for the flames

Whitehall Palace was still a largely timber structure, and flames travelled rapidly from building to building. Before long, flames were rising form the whole of the southern part of the palace.

Image: Reconstruction cross-section through Whitehall Palace in 1547, Crown Copyright Historic Royal Palaces

Fire fighting

As soon as the alarm had been raised, palace staff were mobilised to fight the flames. Pumps and buckets were used to pour water on the burning palace, with little effect.

Massive explosions rocked the evening air as officials detonated gunpowder to create firebreaks, but this made things worse as chunks burning timber fell on other buildings and set them alight. All was chaos.

Image: A 17th-century firepump engine. Sadly the technology of the day was not enough to douse the flames. © Getty Images

Every man for himself

As news of the fire spread, so did the realisation that palace riches were vulnerable. This brought out the worst in some people during the disaster.

Servants who were desperately trying to remove the fabulous tapestries and works of art from the staterooms were shoved aside by looters who had climbed over the palace walls.

Palace inhabitants tried desperately to save their belongings, blocking the way of firefighters.

Did you know?

Among the casualties were a guard burned to death, a gardener blown up, and the Dutch maid who started the blaze.

After the fire

We have William III’s presence of mind to thank for the survival of the Banqueting House that still stands in today’s Whitehall.

Back in January 1698, the fire raged for 15 hours and was extinguished only by the middle of the following day. But a breeze re-ignited the flames in a different part of the palace, near to the Banqueting House.

On William III’s express orders, huge efforts were made to save it. The building’s southern window was bricked up to prevent the flames from reaching the interior.

After the second day, when there was little left to burn, the fire died down, leaving the royal apartments of Europe’s finest palace as little more than a pile of rubble.

Image: William III by Wissing, 1685, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

Except for the Banqueting House and the great gate all is burnt down or blown up…

Fire witness James Vernon in 1698

Learn more about the Whitehall Palace fire

Secrets of Henry VIII's Whitehall

The Archaeology of a Lost Palace

More than 300 years after the destruction of Whitehall Palace by fire, archaeological excavation and scientific analysis continue to uncover the lost stories and secrets of Henry VIII's once elaborate home.

Listen to the podcast

Leech is a man who knows about fire: how it burns, how it feels. But when Whitehall Palace, the largest palace in Europe, becomes the greatest kindling pile for a seemingly unquenchable blaze, even he is left dazzled. Everything burns, even the home of kings.

More episodesBrowse more history and stories

The Rubens ceiling

The crowning glory of the Banqueting House

The execution of Charles I

Tried and sentenced to death for high treason

The masque

A fabulously extravagant early 17th century court entertainment

Explore what's on

- Things to see

The Undercroft

Explore the vaulted drinking den beneath the Banqueting House, which was used by James I for decadent royal parties.

- Closed

- Banqueting House

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Rubens ceiling

Marvel at Sir Peter Paul Rubens' ceiling in its original setting of Inigo Jones' spectacular Banqueting House.

- Closed

- Banqueting House

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)

- Things to see

Inigo Jones' architecture

Find out what remains of Whitehall – known as one of the first examples of Palladianism in British architecture.

- Closed

- Banqueting House

- Included in palace admission (Members go free)